New research exposes the dire consequences of the education gaps experienced by refugee youth in Malaysia, and the wellbeing supports needed to secure them a brighter future.

This year, a staggering 117 million people will be forcibly displaced or stateless, according to the latest estimates from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Driven from their homes by violence, war and persecution, most will endure years of hardship, uncertainty and trauma while they wait for a chance at a safe future in a foreign land.

The outlook is particularly bleak for 185,000 refugees currently in Malaysia awaiting resettlement, Monash Malaysia School of Business PhD candidate Jeron Joseph said.

As a non-signatory of the 1951 Refugee Convention, asylum seekers in Malaysia have no legal recognition or protections, limited work rights and poor access to essential services.

In his comprehensive new study, Mr Joseph has now also exposed the severe lack of education options available for the country’s 50,000 youth refugees.

“Malaysia is only a stopover for these kids, they don’t get to resettle here, so they are stuck in limbo for years on end,” he said.

“After escaping such hardship, they deserve a chance for a better life, but without adequate access to education their futures are at risk.”

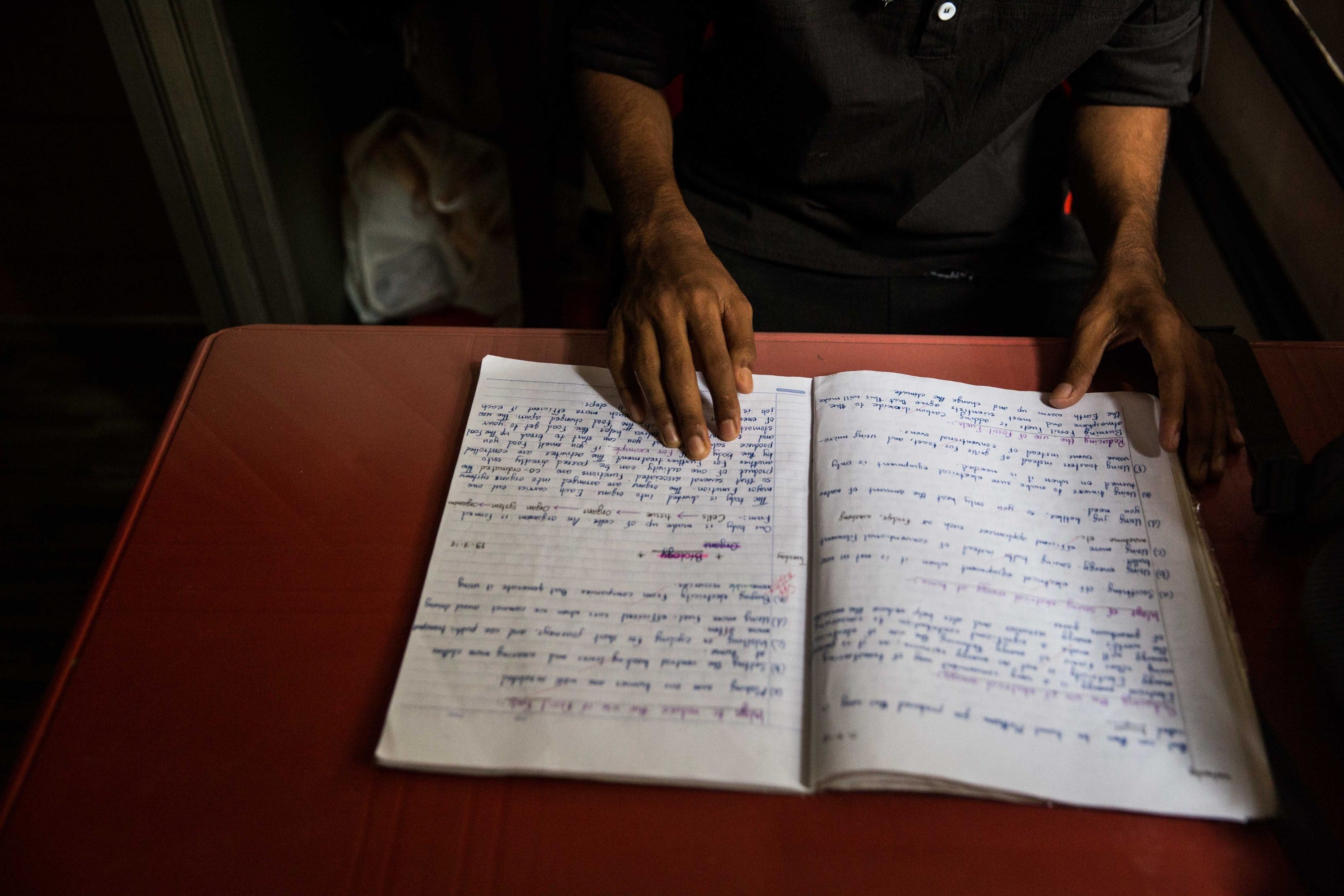

Monash Malaysia School of Business PhD candidate Jeron Joseph.

He said his thesis aims to demonstrate that education is the key to breaking the cycle of poverty plaguing refugee youth in Malaysia.

‘They just want to survive’

Mr Joseph understands what it’s like to be marginalised.

“I come from an indigenous tribe from Sabah, so I know what it means to not be prioritised in terms of policy and opportunity,” he said.

Driven by this empathy, he said the genesis for his research grew out of a decade of hands-on work as a social worker.

“I come from a privileged upbringing where my parents encouraged me to go to school and pursue my dreams,” he said.

“Having worked with people on the ground over many years, I’ve seen that they don’t have the luxury of dreams. They just want to survive.”

Overcrowded and under-resourced

As part of his thesis research, Mr Joseph has mapped the intricate system of secondary schools in Malaysia in order to better understand and overcome the barriers to education facing refugee youth.

His preliminary findings reveal the country’s 143 refugee schools are severely overcrowded and under-resourced. Just 36 are recognised secondary schools.

Services vary widely, from community schools staffed by untrained teachers providing only basic literacy and numeracy to marginally better-resourced NGO-run schools offering a more comprehensive education.

“The system is very loose, and there is a wide range of different kinds of schools,” he said.

“My work shows we need much more structure around how education is provided.”

Through a series of interviews, he has also highlighted the challenges of uncertainty, hopelessness and despair faced by refugee youth waiting for resettlement.

His findings suggest all service providers are grappling with significant youth wellbeing issues such as poor mental health, isolation, hardship and trauma.

An investment in the future

Mr Joseph said his research suggests incorporating socio-emotional learning (SEL) lessons into the curriculum will help to address these struggles.

“SEL has been shown to positively affect academic performance, physical health, reduce the risk of violence, substance abuse, and unhappiness, and address issues relating to gender and cultural roles,” he said.

Refugee educators do not currently have access to this kind of training.

“During my time volunteering, I’ve met so many amazing, committed, motivated teachers who want to learn how to help these kids, but there is nowhere for them to access this training,” he said.

However, that is about to change.

Mr Joseph has secured funding to roll out SEL training for educators at several key community and learning centres in Malaysia.

Eventually, he hopes to see this training taken up more broadly in refugee schools across the country, saying the work will have significant global benefits.

“Malaysia is not the final destination for these kids – they may be resettled in Australia, Canada, the US,” he said.

“I see this as a long-term investment not only for refugee youth but also the countries where they are resettled.”