Eliud Kipchoge drew acclaim by running a marathon in under two hours. But female athletes are setting the pace in pushing the boundaries of physical endeavour, argues Associate Professor Simon Angus.

By any measure, the weekend of 12-13 October 2019 was a huge moment for human athletic achievement.

On Saturday, to international acclaim (and .. ahem .. matching my prediction), the greatest male marathon runner of all time, Kenyan Eliud Kipchoge sensationally ran 1h 59m 40s, the first man ever to go ‘sub-2’ in the marathon.

Kipchoge’s was not an official world-record attempt, and won’t be recorded as such, but, for the thousands of spectators who cheered him on, and the millions who tuned in to watch it live, that detail scarcely seemed to matter.

Then, on Sunday, compatriot Brigid Kosgei broke the official women’s marathon world record in Chicago, in a time of 2h 14m 4s, completing a Kenyan grand-slam.

Both feats are remarkable in their own way, however, with some perspective, one could argue that Kosgei’s was the more momentous.

Not only did Kosgei smash her own personal best of April this year by over four minutes, but she also crashed through the previous, ‘alien’ world record time of 2h 15m 25s, set by Paula Radcliffe in London, 2003.

Kosgei’s effort rightly drew shocked expressions. As reported by The Guardian, American elite athlete, Molly Huddle exclaimed, “2:14 – holy crap, what is life right now?”

But perhaps Kosgei herself made the most startling comment after breaking the tape. “I think 2:10 is possible for a lady,” she remarked.

If ‘life’ was a challenge to define at 2h 14m, what does 2h 10m, or ‘sub 130 minutes’ for the women’s marathon even mean?

Kenyan Brigid Kosgei breaks the women’s world record to win the 2019 Bank of America Chicago Marathon, on October 13, 2019 in Chicago, Illinois.

Crunching the numbers

Earlier this year, I conducted a detailed statistical analysis of the progression of the official men’s and women’s marathon world record.

While the analysis focussed on the official International Association of Athletics Federation’s (IAAF) progression, it provides a powerful lens to understand the dynamics of performance gains in the marathon over time.

Crucially, my study made the link between the question of ‘when’ a given performance would be made and ‘how likely’ that performance would be.

My results showed that within a 10 per cent – or one-in-10 – likelihood, the men’s official world record would not reach the ‘sub-2-hour’ line before May 2032.

While this may seem a while off, it is worth remembering that Eliud Kipchoge’s current world record of 2h 1m 39s (set in Berlin last September) sits 99s outside the ‘sub-2’ barrier.

His Berlin world record run – amazing as it was – sits next to the ‘one in four’ prediction line in my study. In other words, we would have expected to see a run of this kind, on that day in history, with a chance of around 25 per cent.

For women however, we have been living through something of a world record marathon drought.

From Radcliffe to Kosgei and the sub-130 moment

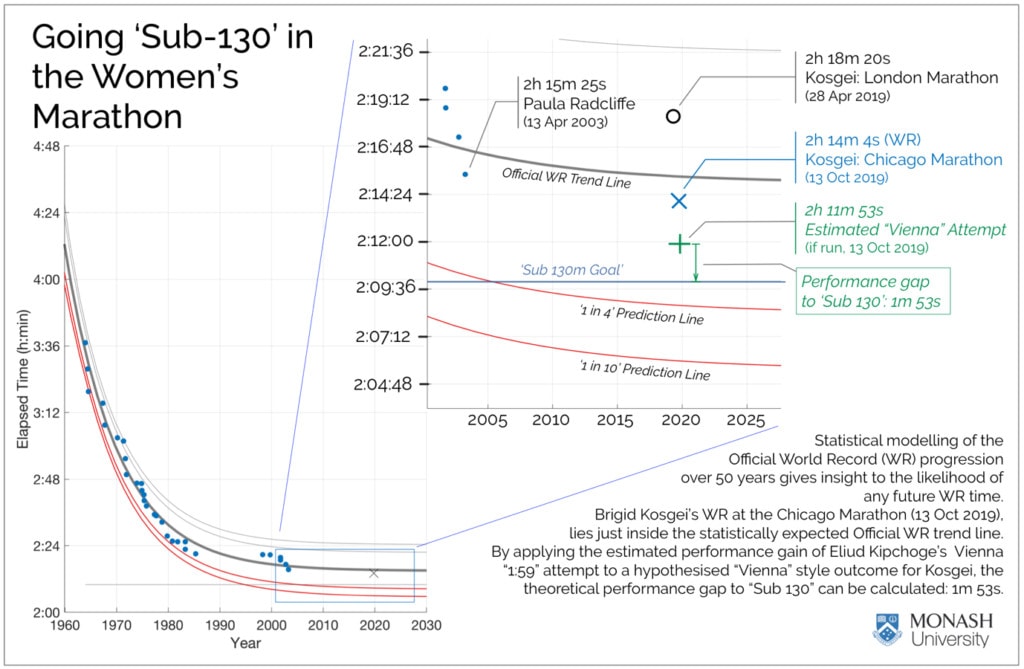

If we apply the same statistical machinery to the female marathon progression, we get results as shown in the figure below.

As can be seen, as ‘alien’ as Radcliffe’s run was, her time of 2h 15m 25s sits just off the average historical progression line for the women’s world record for April 2003.

In other words, given the historical rate of performance gains across all aspects of the female marathon discipline, Radcliffe ran the time one would largely expect for that day in history.

And then, Kosgei.

What’s fascinating to notice is that, like Radcliffe, Kosgei’s new world record time of 2h 14m 4s – a full 81 seconds faster than Radcliffe – sits right near the ‘average’ prediction line.

One could say that 81 seconds of performance gains were to be expected by the forces of performance improvement discovery over that intervening 16 years, the only thing we didn’t know was who would be the runner to harness those gains and mark their name in history.

But we can do more with the analysis.

By zooming in around Kosgei’s time (see above), we get a much better look at what it would take for ‘a lady’ to go ‘sub 130 minutes’.

As it stands, Kosgei would need by simple maths to find 4m 5s to make history.

However, Kosgei ran her world record in an official IAAF race. Kipchoge, on the other hand, went ‘sub-2’ in a somewhat contrived, highly controlled, and extravagantly supported one-off attempt.

It seems reasonable to give Kosgei the approximate performance gain that Kipchoge received from this special effort so that we can make an ‘apples to apples’ comparison.

To do this, we can calculate the performance gain between Kipchoge’s most recent, official world record time (2h 1m 39s, Sep 2018 in Berlin) with his unofficial ‘sub-2’ time (1h 59m 40s).

The answer? 1.63 per cent.

Let’s apply that to Kosgei. We get an expected performance gain of 2m 11s!

It’s not difficult to see why Kipchoge and team were confident as they headed onto the Prater Hauptallee.

And so, here’s the opportunity: Kosgei, if she ran on the same day as her world record, but with the ‘Vienna’ treatment, would have run a 2h 11m 53s marathon.

Running for history?

I’ve argued already that the ‘sub-130’ minute women’s marathon should be considered the equivalent of the ‘sub-2’ hour marathon for men.

And now, with Brigid Kosgei of Kenya, we have a runner who, with equivalent funding, organisation and preparation as Kipchoge’s attempt, stands within 2min of the target.

That’s still a big gap, but Kosgei is not Kipchoge and I think she has a lot more to give.

If you look at the inset, you can see Kosgei’s previous personal best set in April of this year at the London marathon, 2h 18m 20s.

That’s right, Kosgei ran a four-minute PB on that amazing Sunday in Chicago two weeks ago.

Eliud Kipchoge set an official world record when he won the 45th BMW Berlin Marathon in September 2018 in 2:01:39 hours.

In fact, Kosgei is on a huge improvement trajectory, shaving over 30 minutes off her marathon time in the last four years.

As a 25-year-old (to Kipchoge’s 34), Kosgei’s next marathon could well be an improvement of 60 to 120 seconds. In 12 months’ time, there is every reason to believe she could be the one.

Big Marathon, it’s time

Kipchoge’s attempt provides a model of exquisite planning, coordination, coverage and support.

More than 35 elite runners, deployed in five teams of seven, were brought on board to provide metronomic pacing and slip-streaming benefit to Kipchoge.

Two custom-made, laser-casting, precise pacing cars were built for the event; and sponsored product from the top manufacturers in the world were lavished on all runners.

None of this comes cheap, with an eye-watering price tag of £15 million going into the attempt. But Kipchoge’s attempt shows that the extraordinary is possible.

In fact, from the perspective of the historical official WR progression, a sub-130 minute female marathon would fall within the ‘one in four’, or 25 per cent likelihood prediction line.

Contrast this with Kipchoge, who was facing a ‘one in 35’ (less than 3 per cent) chance, relative to the official historical progression of the world record in the men’s marathon.

So history is no barrier to a female sub 130 run. The sub-130 era is now.

Brigid Kosgei has announced that she is ready. The only factor missing is the will to make it happen.

Which global brand has the ambition, the vision, and the commitment to human athletic achievement to see this history-making opportunity become a reality?

Associate Professor Simon Angus is also a part of Monash Business School’s SoDa Laboratories which is an empirical research laboratory in the Monash Business School, founded in October 2018. SoDa applies new tools from data science, machine learning and beyond to answer social science questions from alternative data with a particular focus on internet, text, and satellite data. Among other projects, SoDa Labs is home to the Monash IP-Observatory providing near real-time observations on the activity and quality of the internet world-wide.