The AFL used collaborative governance to address the racial vilification of Indigenous players. What can we learn from this?

In the mid-2000s, Monash Business School’s Associate Professor Lionel Frost was working on the Australian Football League’s official history. As he met with administrators, players and coaches, he began to delve into how the AFL was responding to racial vilification.

“I have a long-standing interest in Indigenous issues and at the time I did several interviews and it got me thinking about the problems,” he says.

Fast forward to 2021 and along with several Monash Business School colleagues, Associate Professor Frost has captured a compelling journey that began with acts of individual player bravery and evolved into a formalised AFL structure that responds to player vilification and continues to work towards removing this form of bullying.

From the individual to the collective

With Associate Professors Pieter Van Dijk and Andrea Kirk-Brown from Monash Business School’s Peninsula Campus as co-authors, Associate Professor Frost’s paper provides insights into how governance structures might improve socio-economic outcomes for Indigenous and other disadvantaged people.

“We set out to understand this process of collaborative governance, and consider how it reveals new information about the generation of resources that will help improve socio-economic outcomes for Indigenous people,” Associate Professor Frost says.

“This can come about through the development of stronger links within and between Indigenous communities and the extension of ties to non-Indigenous people.”

L-R Collective action: Che Cockatoo-Collins, Tony Peek, Ross Oakley, Michael Long, Michael McLean and Gilbert McAdam pose after an Essendon Bomber’s Indigenous Discussion Panel in 2015.

Understanding history

Wicked problems call for collaborative responses, that transcend traditional, hierarchical models of government.

In collaborative governance, stakeholders acquire collective ownership of the process, accepting the outcomes of shared decision-making.

“The AFL Code was the product of a process of collaborative governance,” explains Associate Professor Frost.

“When the rate of participation in elite-level football was low, due to legislative and practical restrictions on the mobility of Indigenous people, Indigenous players could only respond to vilification by ignoring it, retaliating, or withdrawing from the game.”

Few Indigenous Australians played Australian Rules football at the elite level before the 1980s and until 1995, no rules existed as to what AFL players said to each other on the field.

But as the number of Indigenous players increased, a network of those who refused to accept on-field racial vilification developed and by the 1990s, Indigenous players had moved from acting in isolation to working collectively through informal support networks based on shared heritage.

The AFL Commission drew on formal authority to empower Indigenous players, drawing on feedback from them to broker connections with non-Indigenous players.

AFL’s chequered indigenous player history

Opportunities for change were also seized by the AFL, through a collaborative governance approach that empowered Indigenous players. This included strategies for reconciliation and education and the development of anti-vilification rules.

Under the leadership of Ross Oakley, the Commission’s Chairman from 1986 to 1996, the AFL (established in 1990 when the VFL was renamed) tapped a national market.

Video scrutiny and reporting of violent play – along with a blood rule – improved the image of the game, making it more attractive to parents.

The Commission’s strategic planning also included the development of a program to combat racial, religious and gender vilification, although by the mid-1990s this had not been formalised.

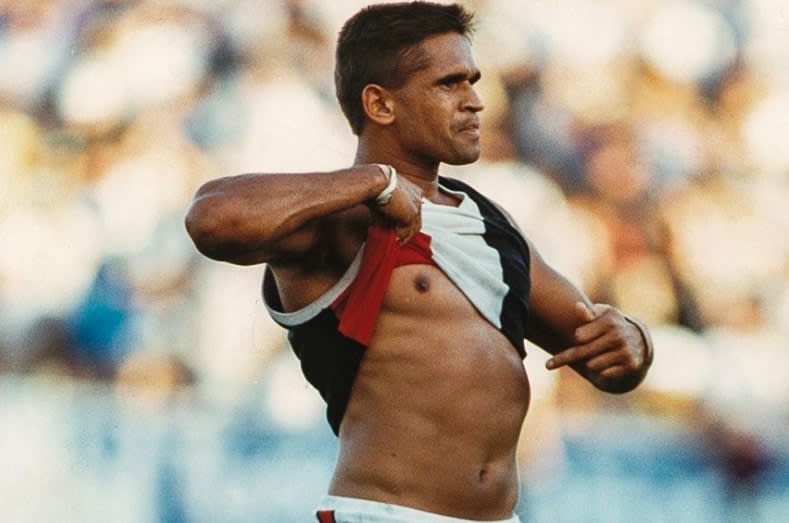

“In 1993, when Nicky Winmar turned at the end of a match to a section of the crowd that had been taunting him all day, lifted his guernsey, pointed to his stomach and declared ‘I’m black and I’m proud to be black’, his spontaneous gesture symbolised the refusal of Indigenous footballers to accept racial vilification as their lot in life,” Associate Professor Frost says.

A moment in history: Nicky Winmar’s 1993 gesture symbolised the refusal of Indigenous footballers to accept racial vilification.

Two years later, Essendon’s Michael Long insisted that his club lodge a formal complaint with the AFL over a remark made to him by Collingwood’s Damien Monkhorst. In it, he explained why racial abuse was so hurtful to indigenous people.

“Although they were supported by other Indigenous players, Winmar and Long were lone heroes, operating at the periphery of a cultural field and lacking the resources needed to seize the opportunity for institutional change,” Associate Professor Frost says.

“While the Commission saw the need for change, collaborative governance was required to engage weaker and disadvantaged groups to ensure that procedures would be effective, and outcomes would be positive.”

The Commission initially directed Long and Monkhorst to a private discussion. Long wanted an apology from Monkhorst, and to test the AFL’s proposed code.

It later transpired that Collingwood’s solicitor had told Monkhorst not to apologise, with Monkhorst reportedly saying ‘You took it the wrong way, mate’.

A model for future empowerment?

From a position of trust and respect within a network of Indigenous players, Michael McLean emerged as a leader who bridged the divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous stakeholders, keeping them involved in collaborative dialogue.

“It was McLean who began the tradition of Indigenous players embracing on the field after a game. It was McLean who began telling racially abusive players he would start naming them in the press. It was McLean who argued that education was needed to create the kind of safe workplace that he would be willing to let his own children be a part of,” Associate Professor Frost says.

Twenty-five years on from the establishment of the AFL’s racial vilification code, player-to-player racial abuse appears to have been eradicated.

But fan abuse at matches and on social media platforms remains a serious issue.

“As debates over how to fix the problems of racial abuse in sport continue, we believe a retrospective assessment of the AFL’s 1995 code of conduct is timely,” Associate Professor Frost says.

“In the future, mistakes from previous policy interventions may be repeated, and any opportunities to understand the design factors that affected the success of collaborative governance initiatives may be lost.”