A unique study of economic history reveals those forcefully uprooted go on to invest in assets they can take with them – such as education.

According to the UNHCR, more than 65 million people are currently displaced from their homelands as a result of wars between nations, civil conflicts or natural disasters.

History, however, may offer a hopeful glimpse or ‘silver lining’ for the descendants of forced migrants.

A study by Professor Sascha Becker from Monash Business School’s Department of Economics with an international team of researchers reveals that Polish people from the Kresy territories of Eastern Poland – uprooted at the end of WWII when these territories were absorbed into the Soviet Union – invested heavily in education rather than material possessions.

The research has found their descendants remain more educated than other Poles – offering a modern roadmap for policymakers when it comes to refugees.

Re-drawing the borders

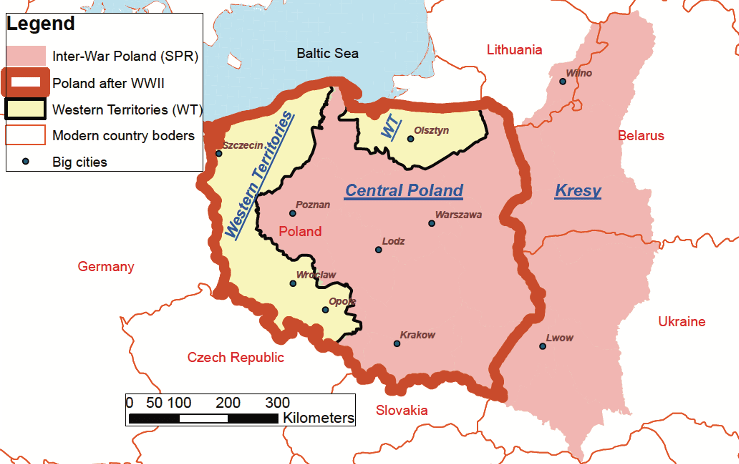

After World War II, a fundamental redrawing of boundaries saw Russia take control of the eastern part of Poland, while Germany ceded the Western territories that had been home to around eight million Germans, forcing them to re-settle, leaving their land and capital stock behind.

Two million Poles from Kresy were forced to resettle within this area in the new Poland, while Ukrainians, Belorussians, and Lithuanians had to leave Poland and resettle in the USSR. These mass migrations began in 1944 and were largely completed by 1948.

Economists have long entertained the idea that being uprooted by force or expropriated increases the subjective value of investing in ‘portable’ assets, in particular in education.

However, research undertaken by Professor Becker, with co-authors Irena Grosfeld and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya from the Paris School of Economics, Pauline Grosjean from UNSW and Nico Voigtländer (UCLA and NBER), has broken new ground by studying the long-run effects of forced migration on the descendants of migrants over several generations.

The changes to Poland’s borders following the end of WWII. Poles from Kresy were forced to move to the western territories, formerly part of Germany. (Source: authors)

Comparing descendants

The researchers combined historical census data with newly collected survey data to discover that Poles with a family history of forced migration are significantly more educated today than other Poles.

The mass population movements of the Poles from Kresy allowed a unique opportunity for researchers to bypass common confounding factors associated with forced migration, such as different ethnicity, language, or religion, as well as congested labour markets, explains Professor Becker.

The researchers accessed the Diagnoza survey, a 2015 large-scale survey from the Council of Social Monitoring to compare descendants of forced Kresy migrants with all other Poles.

However, the survey contains no information about ancestors other than from Kresy.

To address this, in 2016 researchers conducted an additional ancestry survey in the Western Territories where the majority of Kresy migrants were transported after World War II.

They asked a representative sample of about 4,000 respondents about the original location of all their ancestors in the generation of the youngest adults in 1939.

“We obtained the detailed locations of origin of almost 12,000 ancestors from all over present-day Poland, as well as from Kresy,” Professor Becker says.

“In addition, the ancestry survey allows us to compare the education levels of the descendants of forced migrants from Kresy, of voluntary migrants from Central Poland and of Poles who had already lived in the Western Territories before the war.”

Descendants of migrants from Kresy are the most educated, followed by descendants of voluntary migrants. Descendants of the original occupants of the region are the least educated group in Poland’s Western Territories today.

Generational impacts

Descendants of forced migrants have on average one extra year of schooling, which is driven by a higher propensity to finish secondary or higher education.

Since Kresy migrants were of the same ethnicity and religion as other Poles, the researchers were able to bypass some of the confounding factors of other cases of forced migration.

“Survey evidence suggests that forced migration led to a shift in preferences, away from material possessions and towards investment in a mobile asset – human capital. And that these effects persist over three generations,” Professor Becker says.

This type of forced migration can lead to deep emotional scars and trauma that resonates through subsequent generations. Assets that you can take with you become more valuable.

The mechanism behind the ‘education advantage’ of forced migrants also has important policy implications in the face of large refugee flows seen in many parts of the world today.

The shift of priorities towards valuing investing in human capital over physical capital should be used to guide aid priorities.

“A policy recommendation emerging from our study is the proposal that governments in countries receiving refugees should foster access to education,” Professor Becker says.

“While the international aid community does consider education as an important factor in reducing economic and social marginalisation of refugees, our results show that the benefits may be even greater and more persistent than first thought.”