Mental health issues can have little-understood but long-reaching consequences for individuals, families, neighbourhoods. Developing a mental health policy that best utilises our economic resources is crucial for all Australians.

As the Productivity Commission inquiry into mental health examines the effect of mental health on people’s ability to participate in and prosper in the community and workplace, it will also consider the effects it has on our economy and productivity.

Productivity Commissioner Dr Stephen King is heading the inquiry and is trying to get a handle on the costs to Australia due to mental health issues.

While most calculations of the costs simply look at the healthcare side of the equation, Dr King, a former Dean of Monash Business School, says he’s aware it’s the related costs to the broader community that will be the difficult ones to uncover and measure.

Productivity Commissioner Dr Stephen King.

The Commission is currently consulting widely, including in regional Australia. At a workshop held by Monash Business School’s Centre for Health economics earlier this year, Dr King, who is now an adjunct Professor at Monash Business School, outlined how he is hoping to tackle the issue.

“There are other sectors beyond health and a range of supporting services such as housing, education, justice, income support through Centrelink that come into play. We will be considering how governments across Australia can contribute to improving mental health for people of all ages and cultural backgrounds,” he says.

Importantly he wants to know if the government is getting value for money in the way it currently provides resources to mental health and if there are any ideas or suggestions for ways in which it could be improved.

Stigma and discrimination

Dr King, who joined the Productivity Commission in July 2016, says the Commission wants to explore intangible costs including lower social participation, stigma and discrimination, as well as limitation of opportunities and choices, on top of healthcare costs and lost productivity.

“The current situation in Australia we see the biggest percentage of mental health spending is on income support, more so than service use,” Dr King says.

“Approximately 20 per cent of people are suffering from ‘a diagnosable mental health condition’. Most of those are at the mild to moderate end of the spectrum.”

But Dr King concedes that the argument can be dragged down to the severe end very quickly.

“Should we focus on the mild and moderate end or the severe? With suicide rates still increasing, despite investments in suicide prevention in previous years, the severe end of the spectrum cannot be ignored,” he says.

Clear evidence needed

Dr King says the processes and interventions affecting mental health and behavioural consequences can be complex, so evidence needs to be clear.

“Generally, services are disconnected, there is a lack of service navigators and many people have difficulty actually getting into the system, especially in rural areas,” he says.

Among other issues that will be considered includes the government funding systems which have been designed for physical rather than mental ill health.

For example, if someone puts in for a work cover claim, it can be difficult to pinpoint whether mental ill-health comes from work or other prior events or experiences, which is necessary for these claims to go through.

That said, it is the charge of the Commission to look at the mental health care system in Australia with its limitations: it is currently fragmented, not easily accessible, and disorganised. Dr King believes there is much room for improvement.

Current health economics research

Against the backdrop of the Inquiry, Monash Business School’s Centre for Health Economics is leading our understanding of this important issue with a number of key research projects.

Professor Michael Shields, deputy director of Monash Business School’s Centre for Health Economics, is working with its international collaborators in Monash Business School’s International Network on the Economics of Mental Wellbeing to provide much-needed new evidence on this crucial issue.

“It’s research that will improve our understanding of the economic causes and consequences of poor mental health to individuals, families, communities and workplaces. And it is important to evaluate the cost-effectiveness and the efficiency of mental health service delivery,” Professor Shields says.

Smoking behaviour and mental health

Associate Professor Dennis Petrie: “While we have clearly made progress in reducing smoking, the benefits have been for the rich.”

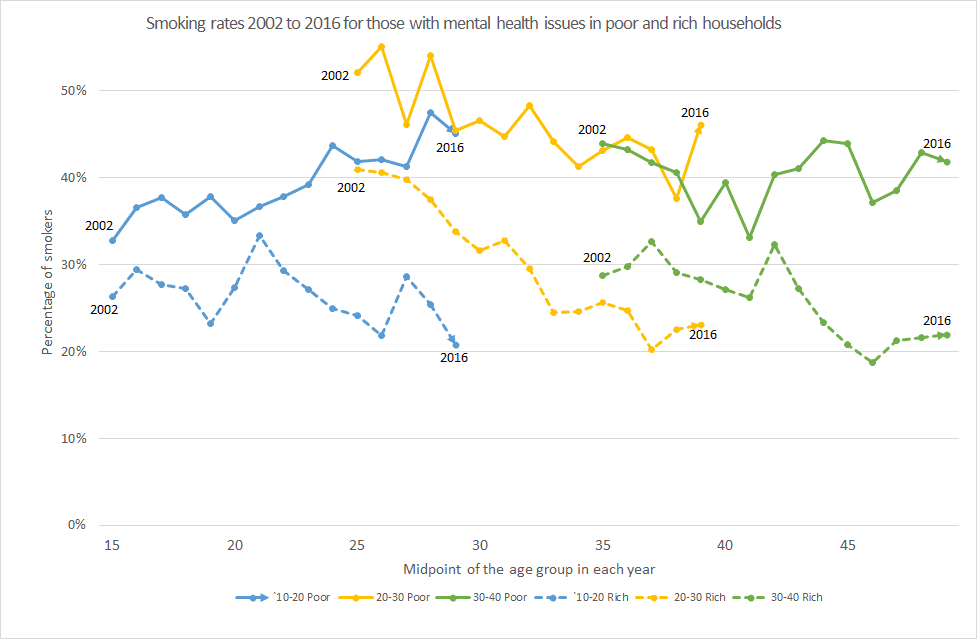

Associate Professor Petrie’s research into smoking behaviour and mental health shows a discrepancy between the richest and poorest households. Over the last two decades, Australia has taken large steps to reduce smoking which has included steep increases in the taxation on cigarettes.

He explains, however, that using data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey from 2001 to 2016, they found that the large reductions in smoking we see over this period have not been uniform across all groups in society.

“For the richest 60 per cent of households, each generation’s smoking trajectory is moving down, with both fewer people starting to smoke and smokers quitting earlier. This is in sharp contrast to the poorest 40 per cent in our society, where each generation follows the past generation’s smoking trajectory,” he says.

For the poor, Associate Professor Petrie says the research shows that for those with good mental health close to 30 per cent are still smoking well into their late 40s while for those with poor mental health smoking rates are close to 40 per cent.

“There is little evidence to suggest that in ten years’ time that smoking rates for the poorest households will have substantially changed. So while we have clearly made progress in reducing smoking, the benefits have been for the rich, while the poorest including those with mental health issues continue to smoke and pay higher taxes,” Associate Professor Petrie says.

“Clearly there is a need for cost-effective policies which reduce smoking for the poor members in our society including those with mental health issues and thus reduce inequalities.”

Opioid use in Australia and mental health

Dr Sonja Kassenboehmer: “Short-term economic downturns at the local area level increase opioid abuse and death.”

Dr Kassenboehmer’s research into the driver of the drug epidemic in Australia shows opioid use has increased dramatically over the last 10 years and is the main reason for overdose deaths.

Countries such as the United States, Australia and Canada have seen sharp increases in the use of prescription opioids over the last 10 years accompanied by a dramatic rise in opioid overdose deaths.

Motivated by the scale and rise of opioid mortality in Australia, her research shows that short-term economic downturns at the local area level increase opioid abuse and death.

Her research provides the first evidence for Australia that the counter-cyclical relationship is likely driven by middle-aged male unemployment.

“Overall, we concluded that economic shocks are only weakly related to rising opioid harm and it is likely that there are a number of other root causes. For example, economic conditions are likely to interact with supply-side factors such as drug availability,” she says.

While the research is still in its preliminary stage, a more conclusive report is expected in the second half of 2019.

How well can childhood circumstances explain later life loneliness?

Dr Claryn Kung: “Childhood health (particularly mental health) can be predictive of loneliness in adulthood.”

Dr Kung’s research on the importance of childhood circumstances on loneliness in later life, using two UK data sets spanning adolescence, young adulthood, and mid-to-late adulthood.

Together with its eight two-yearly measurements of loneliness, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing administers a rich set of life history questions such as childhood socioeconomic status, health, household composition including parents’ marital status, adverse events, and parenting style.

On the other hand, the ALSPAC provides detailed prospective data on these childhood conditions, as well as loneliness captured from ages 11 to 23.

“Childhood health (particularly mental health), maternal relationship, financial hardship, and abuse can be predictive of loneliness in adulthood, with differences seen by gender and age at which loneliness is measured,” Dr Kung says.

Further work is being done on whether there are different patterns of loneliness over time among adults, and whether there exists a fixed and persistent component of loneliness that can be explained by these important childhood circumstances.

Shared suffering? The effect of own and local unemployment on health

Dr Daniel Avdic: “The negative effects of unemployment on health are sensitive to relative concerns.”

While individual unemployment negatively affects a person’s own health, it is unclear how the local environment interacts with it.

Dr Avdic is studying how a high local unemployment rate may reduce the psychological costs of a person’s unemployment but also signal a reduced likelihood of exiting unemployment.

“Using rich Swedish panel data on individuals who were involuntarily displaced due to plant closures, we found that both own (individual) and local (general area) unemployment is positively associated with adverse health events such as increased use of antidepressant drugs, suicides and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr Avdic says.

“However, displaced workers in areas of high unemployment are relatively less impacted compared to displaced workers in low unemployment areas, suggesting that the negative effects of unemployment on health are sensitive to relative concerns. This relative effect is particularly strong for women and older workers,” he says.