Using the sector-wide approach (SWAp) to coordinate global health aid delivers substantial improvements in population health.

International agencies deliver about US$40billion in health aid each year.

But aid can cause problems, as well as offering opportunities.

This is particularly the case when a recipient country is working with multiple donors; delivering aid that may be fragmented, duplicated and poorly coordinated. How can we ensure that health aid is making a difference and delivering health benefits?

Over the past 30 years, a stronger focus on aid effectiveness has lead to a different approach to health aid delivery – the Sector Wide Approach (SWAp).

Sector-wide approach to delivering health aid

The sector-wide approach (SWAp) to health aid has been a key way to operationalise principles for aid effectiveness.

A health SWAp is a formal agreement between an aid recipient government and its donors.

The agreement commits both to a government-led sector-wide health strategy, where donors harmonise processes and rely on recipient-government for financial management.

More than 30 aid-recipient countries have entered into health SWAp agreements.

Our new paper in the Journal for International Development shows that using SWAps to coordinate donors and donor contributions has paid dividends, delivering substantial improvements in population health including a 5-8 percent reduction in infant mortality.

These findings are important because the uptake of aid effectiveness principles remains incomplete – aid fragmentation remains a problem.

When aid is fragmented

When aid is fragmented, the bureaucratic effort needed to manage numerous donors and their reporting requirements may not be proportionate to the funding provided.

Our paper suggests that health SWAps have reduced these inefficiencies, concluding that health SWAps have likely achieved health gains by freeing up domestic resources (health expenditure and health officials’ time).

But criticisms of fragmented aid are nothing new.

By the late 1990s, the inefficiencies and harms from rapidly growing health aid contributions (from an ever-increasing number of donors) were broadly accepted and had been detailed in several prominent critiques.

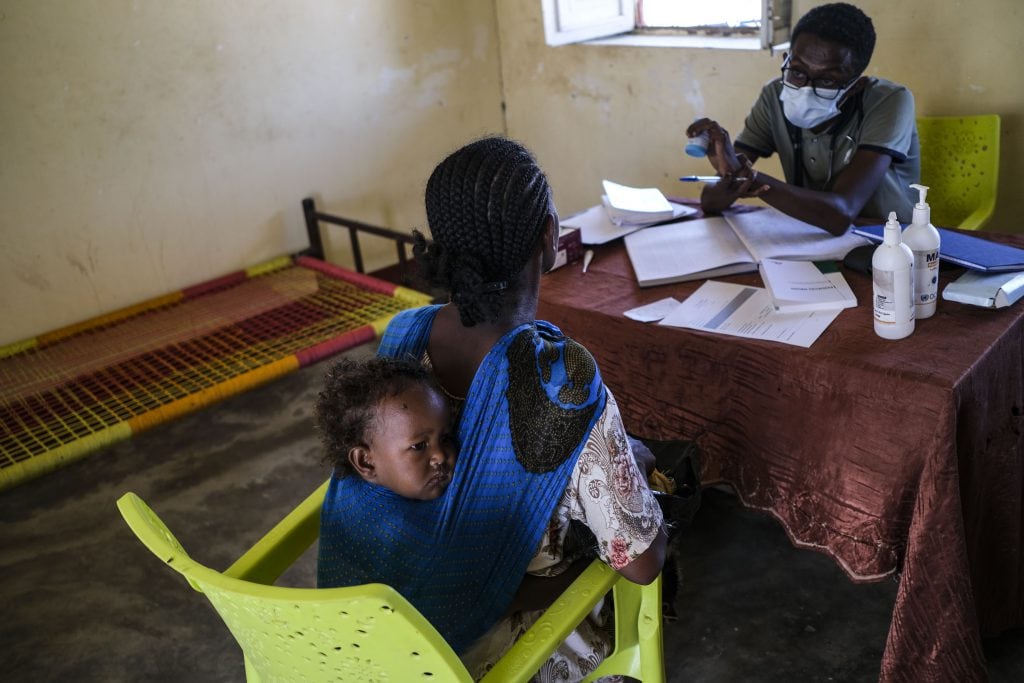

Refugees from the Tigray region of Ethiopia receive basic medical attention from an understaffed clinic in Sudan

Developing an aid effectiveness agenda

In the 2005 Paris Declaration, development partners resolved to do better – by coordinating their contributions, reducing fragmentation, and giving greater ownership of aid management and allocation decisions to recipient governments.

Over the past 10 years, support for SWAps and the aid effectiveness agenda has waned.

One important reason for this has been the lack of robust and compelling evidence demonstrating impact.

Measuring the impact

Some case studies suggest SWAps have increased health aid and made improvements in service delivery and population health. But the evidence was far from compelling.

The problem with case studies is we can’t know if these improvements occurred because of SWAp implementation, or if they would have happened anyway under business as usual. We need a counterfactual.

Credible counterfactuals can be difficult to come by: countries that have implemented health SWAps don’t look like the ‘average’ aid recipient country.

They tend to be poorer in terms of GDP per capita and have worse health outcomes than other health aid-recipient countries.

A SWAp also requires buy-in from the aid-recipient government as well as their key donors, and donor support for SWAps appears to have made SWAp implementation more likely in some regions.

So, the likelihood of SWAp varies across countries and it’s not appropriate to compare SWAp-implementing countries with countries that are very unlikely to ever implement a SWAp.

To control for this, we identified country characteristics that predict SWAp implementation and then made sure our control countries were well matched on these characteristics.

Implementing and control countries might still differ on important but unobservable determinants of health aid funding flows or health outcomes, so we took the further step of controlling for baseline differences in outcomes.

We still don’t have a perfectly controlled experiment, but these steps get us much closer to an ‘apples and apples’ comparison.

The impacts of health SWAps

So, what do we know about the impacts of health SWAps?

First, SWAp implementation can have a significant impact on aid flows.

Specifically, SWAps increased the levels of aid given as general sector support by an average of 360 per cent (granted, from a very small base).

SWAps also facilitated reallocations of aid contributions, specifically away from HIV and maternal and child health.

A plausible explanation for this is that SWAps increased recipient control over health aid and that, in the view of recipient governments, too much aid had been directed towards HIV and maternal/child health relative to other priority areas.

Also, SWAp implementation can leverage more domestic health spending. This is important because donors are understandably concerned that health aid has been used as a replacement for domestic health expenditure in some settings.

Where SWAps are in place, about 70c per dollar of health aid effectively stays in health. This is in contrast to non-SWAp settings, where just 10c to 30c of each health aid dollar stays in health.

Most likely, these gains occur through contractual obligations embedded in SWAps and increased confidence in health sector financial management.

SWAps have positively impacted health

If the primary aim of health aid is to improve health, our new research suggests that the impact of SWAps has been overwhelmingly positive.

SWAps have facilitated, on average, a 5-8 per cent reduction in infant mortality, even in the poorest implementing countries.

Our analysis suggests a likely pathway for this effect is indeed the reducing of the significant burden that comes with managing numerous donors outside of a SWAp.

What this means for policymakers

So where to from here?

After rapid growth in the early 21st century, global commitments of health aid stagnated in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis.

The uptake of SWAps and aid effectiveness principles has stagnated too.

In recent years, a lack of compelling evidence of impact has reduced donor interest in health SWAps and eroded commitment to the 2005 Paris Principles for aid effectiveness.

Our analysis shows that given time to mature, health SWAps can (and have) achieved significant gains across a range of important donor- and recipient-relevant outcomes.

There remains some uncertainty (hard to avoid in real-world policy impact evaluations), and there’s a lot more to learn about the pathways by which SWAps have achieved some of these identified impacts.

But, in an increasingly austere aid environment, these findings should give hope and confidence that efforts to engage with health SWAps appear very much worthwhile.

A version of this article was previously published as a contribution to the DevPolicy blog.