Shareholder activism is on the rise in notoriously confrontation-averse Japan, with knock-on effects on share prices.

What happens when disgruntled investors target Japanese companies?

Until recently, a notable gap in the growing body of research into this area concerned Japan, the second-largest stock market in the world. Does shareholder activism work differently in Japan compared to western markets?

Monash Centre for Financial Studies (MCFS) researcher Dr Nga Pham recently set out to fill this gap to provide investors with a better understanding of activism and its impacts on shareholder returns in Japan.

The study finds that shareholder activism in Japan rewards shareholders with positive abnormal returns, at least in the short run.

This finding suggests that by actively engaging with investee companies, investors could potentially unlock shareholder value.

Japan represents more than 8 per cent to the MSCI World Index, much larger than the UK and Australia. Most Australian investors with a global equity component would likely hold some shares of top Japanese companies like Toyota, Sony or Softbank, either directly or via ETFs.

On the other hand, Australian investors are familiar with large Japan corps via major multi-billion-dollar acquisitions of Australian assets. Asahi’s $16 billion deal on Carlton and United Breweries and Nippon Paints’ $3.8 billion acquisition of Australia’s biggest paint maker, Dulux, are just a few examples among other recent deals.

Anti-nuclear protestors hold banners to voice their opinions to shareholders attending the annual general meeting of Kansai Electric Power Company (KEPCO) in Osaka, Japan.

Shareholder activism on the rise

According to Dr Pham, shareholder activism was on the rise in Japan, at least until early this year, thanks to the introduction of the Stewardship Code and Corporate Governance Code in 2014 and 2015 respectively, and subsequent revisions to both.

“The next wave of change in corporate governance in Japan will be driven by all types of activist shareholders,” commented Tracy Gopal, Principal of Third Arrow Strategies.

“As an increasing number of the 284 signatories of Japan’s Stewardship Code show a willingness to vote against management when warranted, activist activities can be expected to increase.”

The Monash study covered the period of January 2013 to June 2019, with data sourced from the international Activist Insight database.

It examined 246 activist campaigns with 456 public shareholder demands filed on 130 different companies listed in Japan.

Approximately two-thirds of the companies were in the consumer goods, services and technology sectors.

Shareholder activism comes in various forms; it can involve private engagement between shareholders and companies or public campaigns.

Shareholders can press their claims individually or collectively. A campaign often involves a series of demands.

Focus on governance and financial performance

While investors increasingly focus their engagement with companies on ESG issues across Europe, and North America and Australia, in Japan, shareholder activism has been mainly concerned with governance and financial performance.

In the new environment, cash-rich firms with low valuations and low efficiency have become targets of shareholder activism. It is not rare to see a Japanese company with a large amount of cash, some even over 50 per cent of their market cap, yet, offering a low return to shareholders.

Notwithstanding some positive moves in the corporate governance regulatory framework, even today, some institutional and cultural barriers to activism persist.

These include cross-shareholdings, and cultural resistance to shareholder rights, based on a traditional Japanese view that companies’ first obligations are to their employees and customers, rather than to shareholders.

Company responses to shareholder demands

Japanese culture places a high value on social harmony. This is reflected in how companies have been dealing with shareholder demands.

In this context, the researcher noted that Japanese companies typically wait until annual general meetings to respond, presenting practical issues for activist shareholders. Most AGMs are crammed into a short period around the end of June and may last for just 30 minutes, with few questions accommodated.

Companies also tend to avoid public confrontation with shareholders, resulting in only a minority of cases examined in the Monash study leading to public disagreement. The rate of successful and partially successful cases in the study was just 12.5 per cent.

Shareholder activism and investment returns

A key focus of the study was whether shareholder activism was associated with abnormal returns to shareholders.

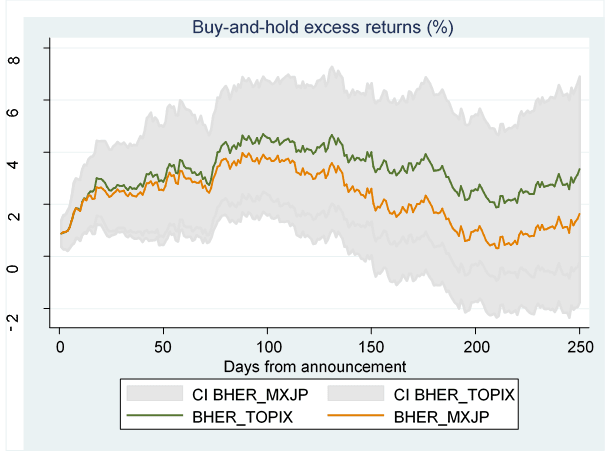

The study found that investors earn a positive abnormal return upon announcement.

By holding it further for up to 120 trading days, investors could earn significant positive buy-and-hold excess returns (BHER) — the return in excess of the market return based on the TOPIX Index or the MSCI Japan Small-Cap Value Index (MXJP).

Beyond 120 days, however, BHERs were not statistically significant.

There were some other key findings:

- Positive short-term abnormal returns are higher for M&A-related activism than for all other categories.

- Activist shareholders with high levels of equity ownership are more likely to succeed in their campaigns than shareholders with lower levels of ownership.

While Dr Pham found abnormal returns linked to activist campaigns do not hold for the medium and long term, she says it does not follow, necessarily, that activism in Japan has had little impact.

“Indeed, the threat of activism may have caused companies to pre-emptively change their behaviour – to be more receptive and attuned to the interests of shareholders to head off the possibility of direct conflict,” she says.

“Additionally, as engagement between shareholder activists and companies often happens behind closed doors, the extent and outcome of this activity could be underestimated.”

A return to the bad old days?

In recent months, the Japanese Government has enacted legislative changes that appear to impose potential new barriers to shareholder activism, particularly for foreign shareholders.

Under changes to the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act, effective June 2020, foreign investors in certain sectors must submit prior-investment notification if they want to join company boards or put proposals to shareholder meetings. The Government also amended the Companies Act to limit the number of proposals submitted by a shareholder at a meeting to 10.

Although the Government insists the amendments would not restrict shareholder rights or engagement with companies, Dr Pham fears otherwise.

“As the impact of these amendments unfolds and companies struggle to recover in the post–COVID-19 world, shareholder activism in Japan may start to wane,” she says.

“These regulatory moves could unwind much of the Japanese government’s efforts at corporate governance reform over the last decade.”