A new paper from eminent industrial relations expert, Professor Joe Isaac, argues that to line up wages growth with labour productivity, the balance of power favouring employers against unions and workers must be corrected.

One of Australia’s most eminent industrial relations experts, Professor Joe Isaac has issued a controversial call for Australia to return to some of its ‘old ways’ – including allowing unions and the Fair Work Commission a greater role to help set wages – in order to achieve appropriate wages growth.

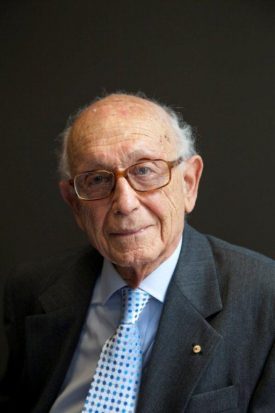

Professor Isaac AO, is Emeritus Professor at Monash University.

Now 96, he has had a distinguished academic career both before and after serving as a Deputy President of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission, a position he held between 1974 and 1987. During his time with the Commission, he played a central part in many national wage cases and continues to be a very active contributor to the debate.

In his most recent paper, published in this month’s Australian Economic Review, the journal of the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, he maintains that the labour market institutions – the unions and the Fair Work Commission – which have in the past been important in driving wages growth, have declined in power.

Union membership is the lowest in Australian history and among the lowest in the OECD. It has fallen from 50 per cent in the 1970s to 15 per cent (10 per cent in the private sector)

The slowing of wages growth has resulted in a significant shift in the distribution of income in favour of higher incomes. According to the OECD, real incomes for the top quintile of households grew by more than 40 per cent between 2004 and 2014, while those for the lowest quintile only grew by 25 per cent.

The policy sometimes put forward to deal with this redistribution of income by appropriate income tax restructuring not only faces budgetary constraints problems, but it does not deal with the underlying problem of wages not sharing adequately with labour productivity.

Underlying factors

Globalisation has resulted in a decline in the manufacturing sector – a traditional area of union recruiting – while changing technology and work practices have also weakened union recruitment. Legislation limiting union power and the Commission’s authority, have contributed to the lacklustre Australian wages growth in recent years.

“To restore the institutional mechanism for wages growth, a return to some of our earlier industrial relations laws may be called for,” he says.

While arguing that the balance of negotiating power now needs to move in favour of workers, Professor Isaac maintains that employers should not fear a return of widespread strike action seen in previous decades.

“Strengthening union presence and power in establishments may create fear in certain quarters that the power will be abused, strikes may return on the scale of the past and wage inflation will take hold. However, there are now prevailing forces, such as global competition and structural changes which will continue to keep union power in check.”

Further, “Giving the Commission the necessary powers to assist in promoting a better power balance also means that it would attempt the exercise of excessive power by either side, labour or employer.”

Professor Isaac notes that bargaining at the enterprise level has fallen by about 40 per cent in the last four years. In 2016, 24 per cent of workers were on awards compared to 15 per cent in 2010.

Enterprise bargaining does not take place for most small and medium-size employers (SMEs) because unions do not have the facilities to deal with individual employers on such scale. A large area of employment is therefore left to individual bargaining with employers at an advantage.

Professor Joe Isaac.

He maintains that multiple employer (MEB) or industry collective bargaining would provide the means to cover the gap in collective bargain in SMEs.

However, while the right to strike in pursuit of agreements under collective bargaining is allowed, no such right exists in industry bargaining.

This is contrary to our obligations under the relevant Conventions of the International Labour Organization to which we are a party. Professor Isaac argues that the right to strike should be restored to MEB on a par with enterprise bargaining.

“Compared to enterprise bargaining, MEB establishes greater fairness and uniformity in pay, in that employees doing the same work are likely to be paid the same or similar wages by all employers covered by the agreement,” he says.

“MEB establishes a common standard for all employers involved— the profitable and the less profitable.

“It takes wages out of competition and forces the less efficient firms, rather than being subsidised by lower wages, to operate at greater efficiency in order to survive, thus raising productivity.”

Union revival?

Professor Isaac also suggests that consideration should be given to legal provisions which, as in earlier years, support the revival of unions such as the reinstatement of union preference clauses, and right-of-entry to unions to check the payments made to union and non-union employees, as well as recruitment of members.

The wide incidence of payment below award entitlements shows the inadequate policing of employment practices which, for many years, were conducted by unions.

“The power of the Fair Work Ombudsman should be expanded to ensure employers are complying with their legal obligations. Legislation should be strengthened against sham contracting – where employers claim someone is a contractor where they qualify as an employee,” he says.

The procedure on intended strike action should be shortened to promote a better balance of industrial power.

Importantly, the powers of the Commission should go beyond determining the Safety Net of award determinations. It should also have discretionary powers to intervene in disputes and conciliate or arbitrate as it considers appropriate as in the past.

Other factors behind the shift in power

The manufacturing industry, a stronghold of union recruitment, has shrunk in the face of competitive imports. Import competition has also placed restraints on unions to demand wage increases.

A growing service sector has opened more opportunities for casual and part-time employment. Enhanced digital technology also allows more people to work freelance or in a flexible arrangement such as Uber.

Over the past 20 years to 2013, the proportion of part-time workers more than doubled. The percentage of casual workers has increased from 17 to 21 per cent from 1992 to 2016. The workers in these and other such insecure employment arrangements are unlikely to join a union.

In 2016, 24 per cent of workers were on awards compared to 15 per cent in 2010. In view of the widespread practice for employers to pay workers below their award entitlements, the 25 per cent overstates the proportion protected by the Safety Net.