The long-term health and economic impact of being exposed to trauma as a child is well documented, however new research by Monash Business School shows that babies exposed to political violence while they are still in the womb also experience health problems later in life.

Using data from China’s Cultural Revolution, the Monash Business School study has found that babies who were in utero during that period have experienced reduced lung capacity and conditions such as asthma later in life.

Long-term health effects

The findings from the paper The long-term health effects of mass political violence: evidence from China’s Cultural Revolution, play an important role in understanding the cause of chronic diseases and how to tackle them from a healthcare policy and economic perspective.

The paper also found that people who were adolescents during the period (1966-68) have higher blood pressure and a reduced ability to engage in everyday activities later in life. For women, that exposure has resulted in reduced lung capacity or asthma in later life. Men experienced reduced cognitive functions or higher rates of dementia or Alzheimer’s as they aged.

“Living in an uncontrollable and unpredictable environment accompanied by the threat of violence causes anxiety and stress to the mother, which can result in biological changes to the foetus. These changes manifest to health problems for that person in later life,” says Russell Professor Smyth, a co-author of the paper.

“The impact is real and it is causing long-term health issues.”

Political violence and trauma

Prenatal stress caused by exposure to violence leads to lower birth weights, and in some cases, premature births, the paper found. Adults born prematurely have been shown to have lower lung capacity later in life, and as a result suffer from conditions such as asthma. Maternal stress at critical times of a foetus’ development can also cause result in a decline in cognitive functions of the brain, the results of which can be felt later in life.

Other studies have proven the link between exposure to other types of trauma such as family violence in utero, and negative health consequences in later life.

In 2015, the Royal Commission into Family Violence heard that children suffer from trauma and physical and psychological damage if they are exposed to violence while in the womb. Expectant mothers who are exposed to family violence also tend to give birth to premature babies, which leads to physical and mental developmental delays.

While Professor Smyth says the findings are similar, his study is the first of its kind to examine a child or babies’ exposure to “political violence and trauma”.

External factors such as salt intake, body mass and alcohol consumption only account for a ‘small part’ of what causes health problems such as high blood pressure. It is important to understand other factors that contribute to health conditions like high blood pressure and asthma, such as stress in childhood.

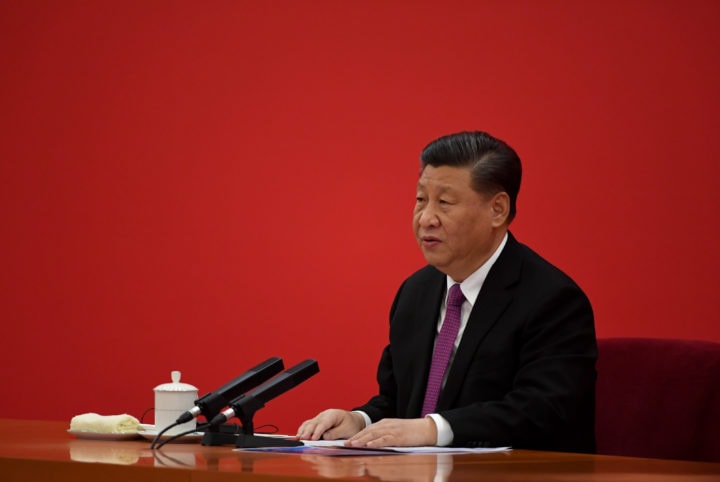

During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Communist leader Mao Zedong attempted to purge “capitalist roaders” and “counter-revolutionaries” from China. Zedong instructed his followers there could be “no construction without destruction”, making it one of the most violent and extreme periods of political violence in history. It is estimated that as many as three million people were killed (Chang and Holliday).

Professor Smyth argues that while not every Chinese person experienced violence first-hand during this time, many were exposed indirectly by the deaths or torture of friends, family and acquaintances.

“This social destructiveness led to a period of mass anxiety. Public brutality was part of everyday life and damaged the country’s psyche,” he says.

Professor Smyth says the research provides an insight into the wide-reaching impact of political violence on health. He says more attention should be given to the potential impact on a child or infant’s future health when they are exposed to such trauma.

“If you look at today’s society, there’s terrorism, war, political unrest, family violence – you name it. The question needs to be asked, ‘What impact is all this trauma going to have on the long-term health of adults in the future?’ ” he says.