Photo: iStock

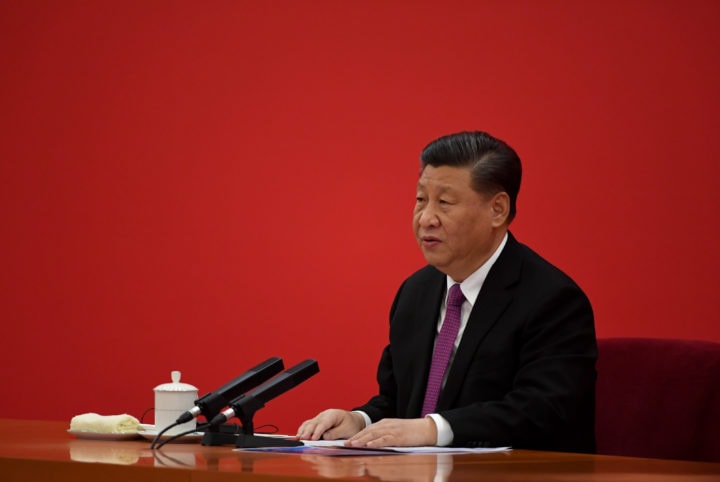

While there are parallels, it is still fraught to compare the China-dominated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank with the (still) US-dominated World Bank.

America’s rise to global dominance occurred over a relatively short period of time following the Second World War. Key to that rise was the Marshall Plan – where the US spent over $13 billion to finance the post-war economic recovery of Europe.

Also contributing to that rise was US control over the development of the World Bank, and US leadership in military and space technology.

Seventy years later, in light of China’s recent “rise” to prominence, is it valid to compare China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) infrastructure initiative to the Marshall Plan?

And if yes, is it similarly valid to compare the China-dominated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) with the (still) US-dominated World Bank?

The answer, as so often the case in an increasingly complex and ambiguous world, is both yes and no.

Yes, because just as the Marshall Plan presented a new vision of US foreign policy in the guise of a practical economic program, so also OBOR presents a vision of Chinese foreign policy in the guise of a practical infrastructure investment program.

George Marshall, as US Secretary of State, understood that an economic crisis produces social dissatisfaction, which in turn leads to political instability. His vision for a stable, connected and prosperous (western) Europe called for the US to take on a permanent role in the construction of international order.

Parallels can be seen in China’s fear of political instability and desire for a permanent role in the construction of international order.

The world of OBOR is a far cry from the world of post-war Europe, and there are consequent dangers in seeing OBOR as China’s Marshall Plan.

A significant proportion of Marshall Plan funding was used to purchase food and other exports from North America, just as a large a large proportion of OBOR funding will pay for Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to take the lead in infrastructure construction projects throughout the OBOR region.

And just as the World Bank became a vector for spreading a US consensus vision of economic development, so also the AIIB has potential to spread a China-led vision of economic development.

But the world of OBOR is a far cry from the world of post-war Europe, and there are consequent dangers in seeing OBOR as China’s Marshall Plan.

Reconstructing a war-torn Europe during the early years of a Cold War is very different to building Asian connectivity in a post-globalisation, multi-polar world. Moreover, America’s short-term Marshall Plan, which lasted for less than five years, was very different to China’s longer-term OBOR vision.

As the World Bank spread the US vision of economic development, the AIIB has potential to spread a China-led vision.

Complex relationships

A key difference between post-war Europe and 21st century Asia lies in the relationships, historical baggage, learning and experience which have accumulated since 1945.

ASEAN, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the EU are all now well-established regional institutions with their own interests to protect, and their own internal conflicts and troubles to contend with.

ASEAN is central to the “21st century maritime silk road” half of OBOR, while both the GCC and the EU are central to the “Silk Road Economic Belt” half of OBOR.

South Asia has its own troubled history and complex ongoing relationships with China. While Pakistan has eagerly embraced its new “Economic Corridor” relationship with China, and been a major beneficiary of AIIB-funded projects, India remains ambivalent, at best, towards OBOR – an ambivalence rooted in the complex history of China -India relations.

Funding for OBOR projects also has to take into account prior learning over the past 70 years of development finance. Unlike the Marshall Plan, which used aid to kick-start European reconstruction, development and growth, OBOR is based on the idea that connectivity can be financed by a mixture of trade, aid and public and private investment.

Funding for individual OBOR projects comes primarily from three main sources: the Silk Road Investment Fund, which is funded mostly by Chinese foreign exchange reserves and operates like a sovereign wealth fund; the New Development Bank (NDB), established by the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) in 2014; and the AIIB.

In a world facing global challenges of climate change, the AIIB’s approach to assessing and managing the environmental impacts of the projects it funds is a vital part of its future.

Both the NDB and the AIIB have entered into cooperation and collaboration agreements with the World Bank and other major regional development banks such as the European Investment Bank.

What this means is that both the NDB and the AIIB have had to develop a full set of working criteria and standards for assessment of project loan applications – including social and environmental standards and guidelines based on international standards.

Most projects funded by the AIIB so far have been co-financed together with the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, and/or the ADB.

Co-financed projects, in turn, have largely been led and managed by the partner institution. This means that most AIIB-funded projects have been managed according to World Bank or similar guidelines governing such things as assessment and management of the social and environmental impacts of funded projects.

In effect, the AIIB is undergoing a process of “institutional learning” from partner institutions as it develops its own set of funding policies and guidelines. What remains to be seen is whether AIIB policies and practices evolve to conform to international standards, or whether they are adapted to suit Chinese preferences.

Greater accountability

There are a number of ways in which China’s domestic financial institutions are now accountable to international standards.

China’s main sovereign wealth fund (which controls 15 per cent of the Silk Road Fund), is China Investment Corporation. China Investment Corporation is a member of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, and a signatory to the Santiago Principles which incorporate concepts of social and environmental responsibility into the investment and lending decisions of sovereign wealth funds.

In a world facing global challenges of climate change, the AIIB’s approach to assessing and managing the environmental impacts of the projects it funds is a vital part of its future.

The AIIB charter declares that fostering sustainable development is among the key purposes of the bank, and its Social and Environmental Framework sets out detailed guidelines for assessing the environmental impacts of projects proposed for lending.

Partner institutions include development banks such as the ADB and the World Bank which have been accredited by the Green Climate Fund , the fund established in 2010 under the UNFCCC.

All of this provides the basis for developing a network of development finance institutions geared towards supervising and controlling (indirect regulation) the behaviour of corporations involved in OBOR projects.

How effectively the AIIB is able to fulfil this role as both financier and “monitor” of infrastructure projects in the region remains to be seen.

The AIIB has the potential to do both good and harm. It is up to all nations, particularly member nations of the AIIB and all nations affected by AIIB-funded projects, to ensure that its potential for good is maximised, while its potential for harm is minimised.

Creating linkages and cooperative arrangements between the AIIB and best-practice global development finance institutions is one way to achieve this. Ensuring that the AIIB itself builds an internal culture of integrity and social and environmental responsibility is also essential. Both require the rest of the world to pay attention to the AIIB.