Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation brought enormous change, but it couldn’t have happened without networks to spread information. Fragments reveal fascinating insights into modern habits.

Networks are everywhere. Of course, today we are used to social networks, where information and ideas can spread at an extremely rapid rate.

If someone sends a meme to two friends, and they send that meme to two friends, and so on, the idea gets to thousands (or more) people with little effort. Social scientists call these ‘network effects’.

But this isn’t an article about modern-day social media. It is an article about networks in history and in particular, those of Augustinian monk and leader of Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther, who lived between 1483-1546.

The Protestant Reformation was a major religious upheaval in the 16th Century across Western Europe that had political, social and economic affects sparking wars, splintering the power of the Catholic Church and setting in place modern Europe.

A university professor as well as ordained priest, Luther published his Ninety-five Theses which rejected core teachings of the Catholic Church. His words and actions throughout his life precipitated a movement that reformulated Christian belief. He is considered one of the most influential religious figures in Christian history.

Although our ancestors did not have the technology to make information spread quite as quickly as we do today, historical networks were still mightily important for all sorts of economic, social, and political processes.

Clearly, it is hard to recreate personal networks, as we need a lot of information about the people in question. Who did they know? How well did they know them? Where were their contacts located?

This is hard enough information to get for people in the contemporary world (unless you work for Facebook). It is next to impossible to get for most historical figures.

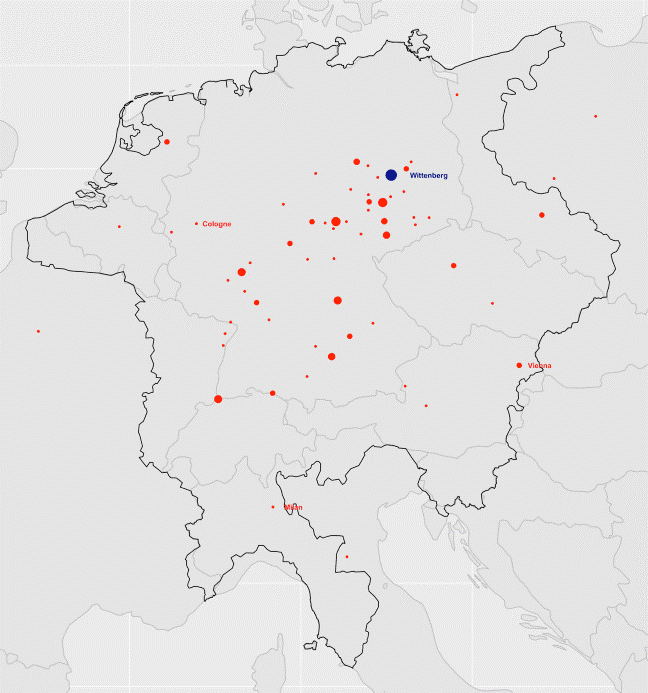

Fortunately we are able to gather together fragments through the work of past and present scholars. For instance, due to the meticulous life-time work of a German theologian Georg Buchwald, we know each city Martin Luther visited and when he visited it. And from the work of US researchers Hyojoung Kim and Steven Pfaff, we know the location of each of Luther’s students at the University of Wittenberg.

While this data of course does not tell us every person Luther ever met, it does give us a pretty good indication of whom he had some influence.

Luther’s network and the spread of the Reformation

Luther was influential. Whom he was connected to may have therefore mattered.

We can conceive of the process as leader-to-follower, originating with Luther and flowing to local elites through personal ties. Luther played the role of a global opinion leader based in Wittenberg.

He had ties with local elites in towns across Central Europe, who, in turn, exerted influence in their towns.

But the Reformation may have also spread independently of Luther.

Because it was costly to adopt, towns were only likely to adopt if they were connected to another town, via a network, that also adopted. We could therefore envision the Reformation as a “virus” that spread out of Wittenberg. It is certainly a possibility we cannot discount without evidence.

So, which was it?

Was Luther completely unimportant to the spread of the early Reformation? Would any “heretical” movement coming out of Wittenberg have lit the anti-papal fuse, even in the absence of Luther?

This is unlikely. As we show below, Wittenberg was not very well connected within the Holy Roman Empire (via trade routes). It was, in Luther’s words, “on the edge of civilisation”. So maybe the trade network was not enough to spread the Reformation.

Recreating Martin Luther’s network

The 16th Century Protestant Reformation was a classic situation in which networks might really matter. Initially, adopting the Reformation was costly.

Protestants were burned alive and religious warfare was endemic. This is where networks may matter.

When adoption is costly, knowing that your neighbours adopted is useful—at least you will have allies. Networks also help facilitate the spread of information, which is incredibly important for a movement steeped in ideology.

Fortunately, Luther left enough traces to recreate his network.

In a recently-published paper with sociologists Yuan Hsiao and Steven Pfaff, we attempt to understand the role that Luther’s network played in the spread of the early Reformation.

In one sense, we were lucky we were able to do this. Luther was an important person who has fascinated historians for centuries. As such, there has been much work done by a panoply of historians documenting numerous aspects of Luther’s life.

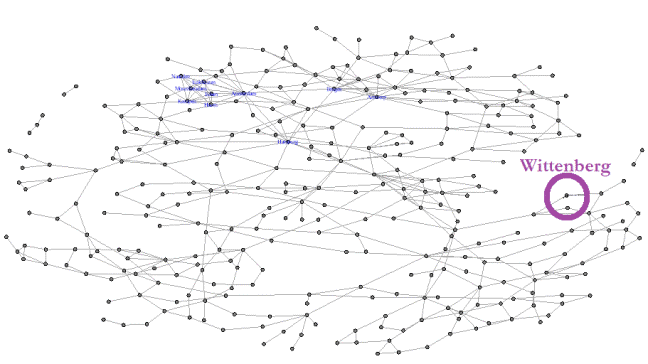

Many of the letters he wrote survived and have recently been digitised. For the sake of reconstructing Luther’s spatial network, we coded every city in which Luther sent a letter (see below).

But was Luther’s network enough, on its own, to account for the spread of the Reformation?

Here, our analysis also finds little evidence in favour of this theory. We conducted a simulation analysis and showed that Luther would have had to have been improbably ‘infectious’ for his network to fully explain the spread of the Reformation.

That is, way too many nodes in Luther’s network would have had to adopt the Reformation because of Luther (and not a myriad of other causes contributing to the success of the Reformation) for this to be the dominant explanation.

So, did Luther’s network matter at all? In short, yes. We argue—and our simulations and regression analyses support—that personal/relational diffusion via Luther’s network combined with spatial/structural diffusion via trade routes.

But it was the combination of the two diffusion processes that helped Protestantism’s early breakthrough from a regional reform movement to a general rebellion against the Roman Catholic Church.

Multiplex ties point to how Luther as an opinion leader mobilised his personal network through an ensemble of letters, visits, and student relationships.

It also shows how Luther’s network blends with the spatial (trade) network to create complex contagion processes operating at the intersection of information flow and social influence.