Judges in authoritarian regimes are often considered puppets. But fascinating research about the motivations of the notorious People’s Court judges has uncovered a stunning truth.

The US court system has to-date proved itself to be a major irritant to the Trump administration, blocking and stalling numerous aspects of its agenda.

Yet, can such judicial independence be guaranteed if the society in which it is embedded is becoming – as many fear in the US – more authoritarian?

In other words, do judicial courts in authoritarian regimes inevitably act as puppets for the interests of a repressive state – or can judges even in these contexts act with at least a modicum of independence? And, if so, what factors influence their decisions?

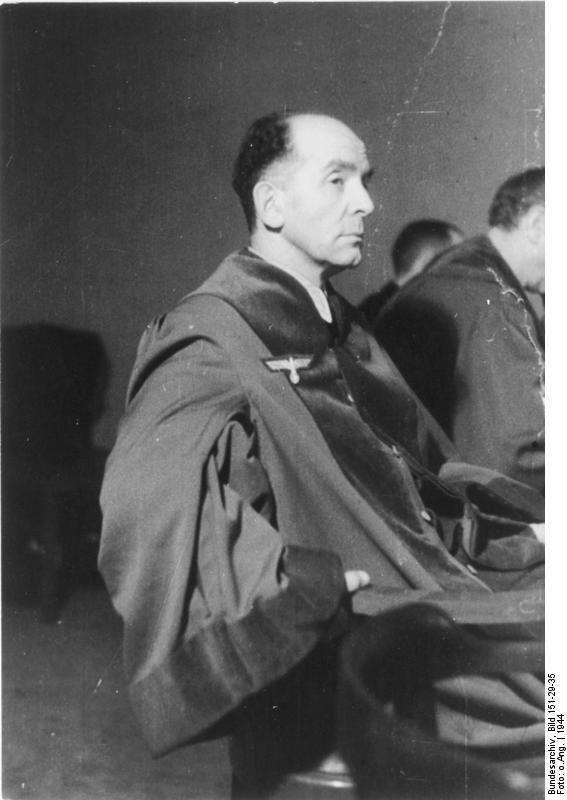

The People’s Court

A study of Nazi’s Germany’s notorious People’s Court to be published in the prestigious Economic Journal reveals direct empirical evidence of how the judiciary in one of the world’s most notoriously politicised courts were influenced in their life-and-death decisions.

The research team, made up of Dr Wayne Geerling from the University of Arizona and Professors Gary Magee and Russell Smyth and Associate Professor Vinod Mishra from Monash Business School, examines the factors influencing the likelihood of imposing the death sentence in Nazi Germany for crimes against the state – treason and high treason.

The research provides important empirical evidence that political and ideological affiliations and the earlier life experiences of these judges played a key role in sentencing, a finding that has applications for modern authoritarian regimes and also for democracies which administer the death penalty.

It presents direct empirical evidence for the first time of the reasons behind the use of judicial discretion and why some judges appeared more willing to implement the will of the state than others.

The team examined data compiled from official records of individuals charged with treason and high treason who appeared before the People’s Court, until the end of World War 2.

When the Nazis came to power in January 1933, cases of treason and high treason were tried before the Supreme Court (the Reichsgericht). But the Reichstag fire, an arson attack upon Germany’s Parliament, on February 27, 1933, provided the catalyst for the Nazis to significantly weaken the Supreme Court’s judicial powers.

The regime blamed Communists for the fire. But when four of the five defendants were acquitted for lack of evidence, a furious Hitler labelled the judges as ‘senile’. The Nazis then established the People’s Court and transferred jurisdiction for cases of treason and high treason.

More than simply ‘blood tribunals’?

The People’s Court has been vilified as “blood tribunals” in which judges simply meted out pre-determined sentences. But in recent years, while not contending that the People’s Court judgments were impartial or that its judges were not subservient to the regime, a more nuanced assessment has emerged.

Just how willing judges were to implement the will of the authoritarian state depended on how closely their own political ideology aligned with that of the regime.

While all the judges in the analysis belonged to the Nazi party, this in itself did not completely explain how judges would act – many would have been expected to join for career advancement. However, judges with a deeper ideological commitment to Nazi values – typified by being members of the Alte Kämpfer (‘Old Fighters’ or early members of the Nazi party) – were indeed more likely to impose the death penalty than those who did not share it.

“The Alte Kämpfer held personal views that were strongly aligned to the values of the Nazi Party,” says co-author Professor Gary Magee. “Given they had all joined the party before its seizure of power, their dedication to the movement and its causes was in most cases deeply held.”

Overall, these judges moved most harshly against Communists, the regime’s political enemies – although this was nuanced. In the earlier years of the regime, before the invasion of Russia in June 1941, Communists had been statistically less likely to receive the death penalty. Communists had also been less likely to receive the death penalty during the period of the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union (August 1939 to June 1941).

The authors suggest this was likely an attempt to avoid an escalation of resistance or build bridges to individuals within the Communist movement who might still be convinced to accept Nazi rule.

‘Repellent to core Nazi beliefs’

As well as acting harshly against members of the most organised opposition groups and those involved in violent resistance, these judges were also more likely to hand down death penalties to “defendants with characteristics repellent to core Nazi beliefs”.

These of course included Jews, but devout Roman Catholics, defendants with partial Jewish ancestry, juveniles, the unemployed and foreigners were also put to death.

“Nazi ideology was also deeply antagonistic towards all organised religion, especially those varieties, like Roman Catholicism, which sought to maintain their independence from Nazi control and influence. Individuals who attempted to assert Roman Catholic values in place of Nazi values were thus harshly persecuted,” the research says.

And while youth and economic disadvantage might in other circumstances be seen as mitigating factors in sentencing, Nazi doctrine decried and called for the ruthless expunging of any element of German society that acted to hold it back from achieving its ‘destiny’. So Alte Kämpfer judges would have shown markedly less sympathy.

Judges whose early adult lives were affected by the upheaval of the German Revolution in 1918-1919 and who lived through the Weimar Republic’s notorious period of hyperinflation – June 1921 to January 1924 – were more likely to impose the death sentence.

Even where they lived had an impact: Alte Kämpfer members whose hometown or suburb lay near a centre of the Revolution of 1918–9 were more likely to sentence a defendant to death.

Modern authoritarian regimes

Existing economics literature on sentencing in capital cases has focused mainly on gender and racial disparities, particularly in the US.

But the understanding of what determines courts in modern authoritarian regimes outside of the US to impose the death penalty is scant. Studying a politicised court in an historically important authoritarian state sheds light on sentencing more generally in authoritarian states.

“Our findings are important because they provide insights into the practical realities of judicial empowerment by providing rare empirical evidence on how the exercise of judicial discretion in authoritarian states is reflected in sentencing outcomes,” Professor Magee says.