Even if they were never intended to cause harm, some business decisions can lead to human rights abuses.

That’s why educating future leaders to think about the consequences of their actions is critical. Understanding basic business human rights is important in a global economy.

There are many well known and tragic examples of what can happen when businesses do not respect human rights. Two notorious incidents are the collapse of Rana Plaza complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2013, which killed over 1,300 people; and the 1984 toxic gas release at the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, which caused the death of up to 3,800 people.

But some businesses are directly or indirectly involved in human rights violations on a much smaller scale, every day. They may be engaging in disability discrimination in the workplace, for instance; or one of their suppliers in their extended value chain is using forced labour.

Yet in many cases, company directors or their employees may not knowingly have made decisions that impact negatively on human rights.

Leading business schools, including Monash, are now offering students classes in business and human rights. Why do business students need to know about human rights? Aren’t these the domain of the State?

Google and Apple

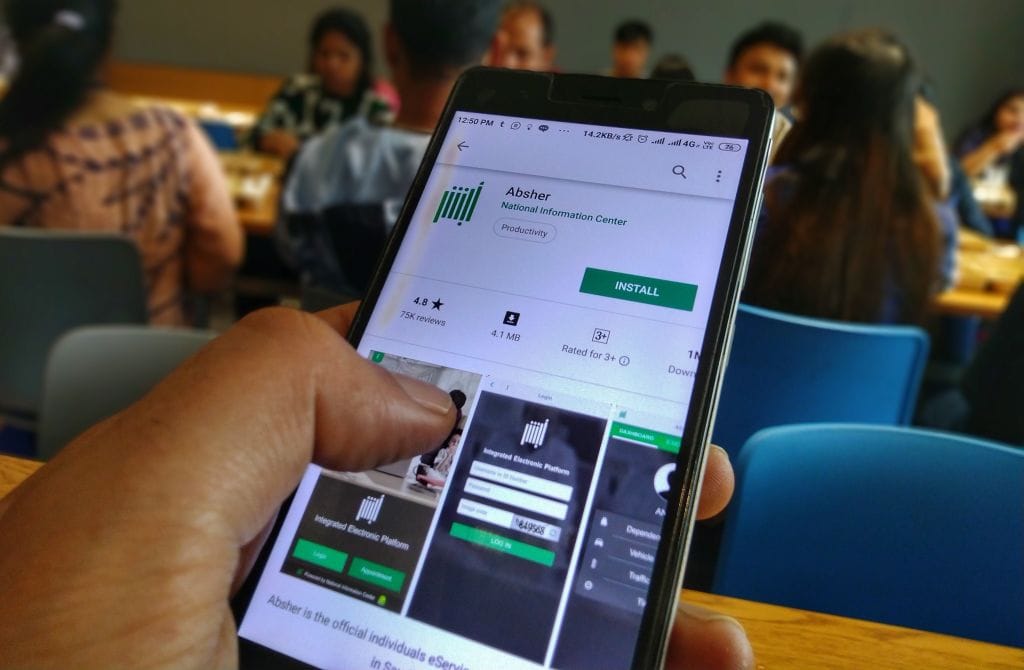

Google and Apple both experienced what can go wrong for businesses when they came under fire recently for perpetuating gender discrimination inherent in the Saudi male guardianship system.

Available on both tech giants’ platforms, the Absher app – developed by the Saudi Government – enables men to monitor and manage the women under their ‘guardianship’ by updating or withdrawing permission for their wives and female relatives to travel internationally and receiving SMS updates if women do use their passports.

This case has sparked debate over the adequacy of Google and Apple’s human rights policies and terms of service, amid high profile calls for the app to be withdrawn.

But increasingly businesses are facing these sorts of questions: what policies do you have in place to ensure you are respecting human rights? What processes have you developed to ensure you can identify and respond to possible human rights risks in your activities and commercial relationships? How are you going to respond to allegations of involvement in human rights violations?

Role of education

All this suggests that human rights will only become a more salient issue for businesses in the future. At Monash Business School, we want to ensure our students are ready to meet these challenges by empowering them to recognise and engage with human rights issues in whatever role or industry in which they work.

Recently Monash Business School co-hosted an address by Professor John Ruggie in Melbourne.

Professor Ruggie is Berthold Beitz Professor in Human Rights and International Affairs, Harvard University. From 2005-2011 he served as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Business and Human Rights. His mandate, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, was unanimously endorsed in 2011.

In his address, Professor Ruggie explained how he and his team went about developing the Guiding Principles and how they have become the most authoritative global standard for responsible business conduct today.

He says there has been a swift and broad take-up of the Guiding Principles by governments, businesses and civil society around the globe.

“The concept of corporate human rights due diligence, in particular, has been embraced by many of the world’s leading multinational companies and is also finding its way into ‘harder’ forms of law at the national level,” Professor Ruggie says.

Human rights abuse and reputation management

There is also a growing recognition by businesses themselves that failure to take human rights into account may impact negatively upon business value.

There is a long-standing debate over whether there is a ‘business case’ in quantifying the benefits or costs of investment in human rights. Today, the financial implications for companies remain poorly understood and more research in this area is needed.

But there are compelling reasons for companies to take a longer-term view around human rights. A company’s reputation can be considerably damaged by adverse human rights impacts and their resulting publicity. Relationships with employees, suppliers, consumers, unions and NGOs can be affected, while investor and lender scrutiny of corporate human rights performance is also intensifying.

What is BHR?

While business schools already teach Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Business and Human Rights (BHR) is different.

In many ways, BHR has emerged out of a critique of CSR. Critics argue that CSR lacks clear standards, that it ‘is whatever companies want it to be’, and often, ‘what is most convenient’.

The focus of CSR on raising standards of corporate conduct by reforming the company from within has been proven inadequate. Greater legal and regulatory oversight is necessary.

The central focus of BHR is to hold businesses accountable for their negative human rights violations and impacts. This includes where they inflict the harm directly and where violations occur down the supply chain by affiliates, subcontractors and suppliers.

Unlike CSR, BHR has a clear and identifiable normative basis in international human rights law.

Another recent visitor to Monash Business School, Dr Dorothée Baumann-Pauly, Research Director at NYU Stern Centre for Business and Human Rights sums up the key difference between the two approaches. While CSR is often about how companies spend their money, “BHR explicitly focusses on aligning a company’s core business processes and models with their commitment to human rights,” Dr Baumann-Pauly says.

“BHR asks companies how they are making their money, not how they are spending it.”

Australian perspective

Business and human rights is a rapidly growing field in Australia. In 2018, the influential UK-based Business and Human Rights Resource Centre appointed its first regional representative for Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific.

On the public policy front, Australia now has an Annual Dialogue on Business and Human Rights, which brings together business, investors, government, civil society and academia.

Australia is also strengthening its ‘National Contact Point’, or AusNCP, the office responsible for receiving complaints against companies for failing to comply with the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises.

This local momentum means it is increasingly likely that Australian businesses will be caught out, within Australia or abroad.

ANZ learned this the hard way when its financing of a Cambodian sugar plantation was linked to forced evictions, child labour and dangerous working conditions, leading to two NGOs to lodge a formal complaint with the AusNCP against the bank.

In its final statement issued late in 2018, the AusNCP concluded the potential risks associated with the bank’s decision to take on the client ‘would likely have been readily apparent,’ and that ANZ had failed to comply with its own human rights standards.

Recent human rights-related shareholder resolutions at large Australian companies such as Woolworths and Qantas are also good indications of increasing awareness and activism on business and human rights in Australia.