While service robots can lower costs and improve efficiencies, we’re not ditching human interactions just yet.

Imagine the following scenario.

You are staying at a hotel and would like to have brunch. Usually you ask the hotel concierge for recommendations.

But as you approach the concierge desk, you see both a human concierge and a service robot.

What would you do? Use the robot or talk to the staff?

New research from Monash Business School shows people react differently to robots – so it is critical to take into account how and when consumers are likely to prefer them.

Professor Yelena Tsarenko and Associate Professor Dewi Tojib of the Department of Marketing have studied what motivates consumer behaviour when it comes to dealing with service robots.

“With wider penetration of service robots in our daily lives, customers are getting more comfortable with being served by androids,” Professor Tsarenko says.

“However, unpacking factors that influence customers’ openness to interact with service robots is of interest to both academics and managers.”

Growing market of service robots

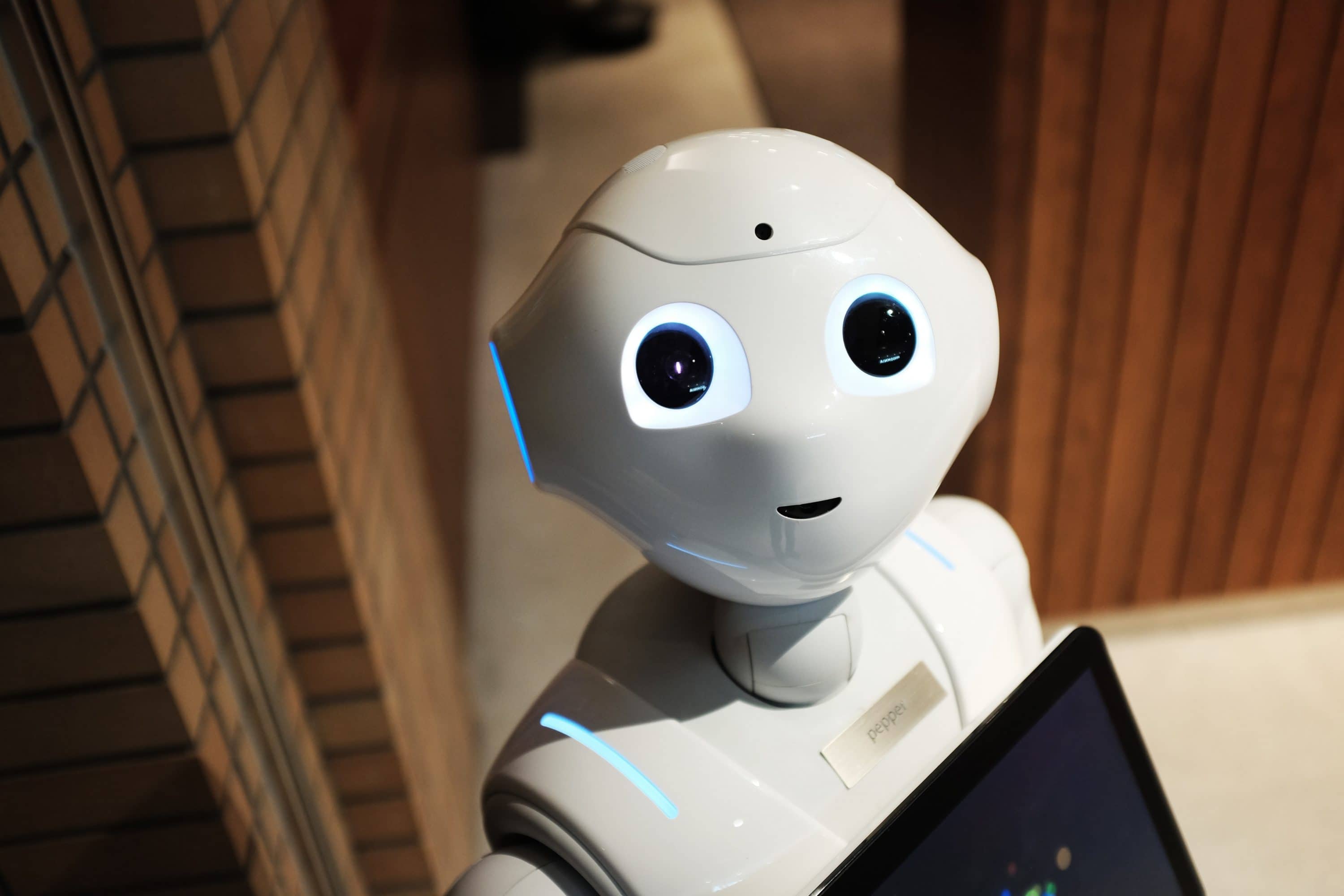

The use of service robots– automated technology shaped like a human equipped with some degree of Artificial Intelligence (AI) – is set to boom, with the market estimated to increase to $34.4 billion by 2026.

But while service robots show great potential to enhance customer experiences people in general, the challenges lies in helping people become more comfortable with the idea of using them.

Service robots generally have adaptable interfaces allowing them to interact and communicate with customers, with the AI integration allowing them to ‘learn’ to improve functional performance.

Service robots can now ask clarifying questions, recover customer errors, provide counter-intuitive solutions and better respond to socio-emotional cues such as providing sympathetic responses and gestures depending on customer emotions.

This makes service interactions more similar to those experienced with human staff.

How well we accept services robots depends on how capable we feel around them.

Don’t embarrass me: Why we avoid or accept service robots

While most research in this area has focused on classic technological and psychological factors of innovation adoption, Associate Professor Tojib explains the uniqueness of this research is that it considers individuals’ mental frameworks – how they interpret and evaluate situations when they either accept or avoid using service robots.

“This is particularly the case when they are around other people. This is important given the predominantly public nature of service robot use,” she says.

“Some people think, ‘If I use the robot, I can show my competence to others’. These people are confident that they will perform better than others. But other people think, ‘I cannot show my incompetence to others’.

“These people will feel embarrassed if they perform badly when interacting with the robot. This can explain why some people are keen to try the robot, while others prefer the old way of interacting with the service firm.”

An important factor in service robot use is age. Associate Professor Tojib says the average age of participants in their study was 38-41.

“Individuals need to feel highly motivated to choose to interact with a service robot over human staff,” she says.

“Our study shows that most people are not scared of robots anymore. But if we had surveyed older people this may have been different. That is because they may have been embarrassed about using a robot. It comes down to a change of mindset.”

Understanding how consumers perceive their own competence

Associate Professor Tojib suggests that firms need to understand how consumers perceive their competence – their motivational drivers – in using service robots. Based on this evaluation they can either resist or be more open towards using the robot.

“Although service robots are increasing in popularity, customers who have not yet been exposed to them may lack a frame of reference when asked to evaluate their use,” Associate Professor Trojib explains.

That’s why the researchers focused on anticipated emotions as part of task appraisal.

They construed challenges and threat appraisals as anticipated positive and negative emotions, respectively.

“This approach aligns with prior research that establishes anticipated emotions as a point of reference for beliefs about the consequences of using an innovation,” she says.

“Our research results confirm and validate the notion that anticipated emotions in particular the anticipated positive emotions, are the underlying mechanism that explains innovation adoption.”

What’s your preference?

For firms wanting consumers to use service robots, the researchers found that they need to make less-resistant people more confident that they can use them without embarrassment.

The key to this is showing how others used the service robot, and make the experience more fun.

“If we look at the opening scenario, you are in a hotel lobby and unsure whether to use the robot or the human staff, it would be good for the hotel to have a video of others using the service robot,” Associate Professor Tojib says.

“This will give them a glimpse of what the experience will be like. Then, they go – ‘OK this is actually not so bad! I can do this’ – building up their confidence in trying new things.”

What the study revealed about our motivations

The study exposed customers to service robots for the first time, along with a more familiar alternative (human staff) that allowed them to interact with the service firm.

The results showed that when firms do not expose customers to social influences, such as seeing others use service robots, their decision to choose service robots rather than human staff is affected by their motivations and whether or not they feel confident of achieving their outcome.

“Customers with high desire for achievement will show a higher level of adoption compared to those with high desire to avoid failure,” Professor Tsarenko says.

This is because high achievement-oriented customers frame their interaction with service robots as the achievement of a desired state – to show their high competence in their interaction with service robots.

“These customers believe that they can interact with service robots successfully, which later encourages them to choose service robots instead of human staff,” Professor Tsarenko says

On the other hand, high ‘avoid failure’-oriented customers frame their interaction with service robots as the avoidance of an undesired state – to prevent them from having a negative experience that can trigger negative judgements from others.

“Therefore, they are less likely to want to use service robots,” she says.

How firms can help consumers choose robots

“Individuals view their encounters with the service robots as a performance situation— one that determines whether they will adopt or resist the innovation.

This means that only when customers perceive themselves as competent (relative to others) and anticipate positive emotions, will they consider using the innovation.

“Firms should ensure that customers are high in ‘desire for achievement’ orientation when first being exposed to technology innovation,” Professor Tsarenko says.

“Our successful manipulation of performance goal orientation suggests that firms can actually create an environment that drives their customers toward a ‘desire for achievement’ orientation.”