Just about every book on starting a company tells you to set up a budget and keep a close watch on the finances. But surprising research suggests establishing the right culture may be better for fostering growth.

Sometimes maxims are wrong. Just as your mother may not have been completely correct when she said to eat your vegetables to grow strong, new research shows that there are other ways to grow a successful business rather than just focusing on your financial controls.

Using a case study of an anonymised New Zealand entrepreneurial company, Monash Business School’s Associate Professor Ralph Kober from the Department of Accounting says what they discovered in their research runs counter to the prevailing understanding on controls.

“While financial controls are important to rapidly scale a business, we did not know how these controls emerge in entrepreneurial companies in relation to other management controls,” he explains.

The collaboration came about following a chance conversation between Associate Professor Kober and one of the company’s founders at the Deloitte Fast 50 awards night.

Despite the informal nature of the exchange, the founder surprised by following through with his promise to open up the company to the research team, which also included Assistant Professor Chris Akroyd from Oregon State University’s College of Business and Master’s student Danni Li.

“He said it was important for him to keep his promises as this was a key part of their culture,” Associate Professor Kober explains. For this business, culture was everything.

Rapid growth

Upon request from the founder, Associate Kober agreed to keep the name of the company anonymous, but dubbed it ‘Company Z’.

Company Z manufactures, sells and installs ventilation systems that are markedly different from others on the market. It takes the filtered air from the roof cavity and pumps it into the home.

Established in 2003 in the garage of one of the two founders, the rapidly scaling company experienced skyrocketing growth of 732 per cent from 2004 to 2006, with business revenue rising from NZ$100,000 in its first year to NZ$$7.23 million in 2006. By the end of its sixth year, it had reached NZ$19 million.

Examining the package of management controls that emerged during this early phase, Associate Professor Kober was struck by two things: the deliberate lack of financial controls and the emphasis on company culture.

“When I met the founder, he said something that I thought was quite interesting – ‘there’s no risk in growth, as long as you grow’. I wanted to know how they achieved such growth. What emerged was a strong emphasis on culture,” he says.

The founders had begun the business with a little start-up cash from their own savings and a strong sense of wanting to build a family-esque organisation where trust and commitment meant something.

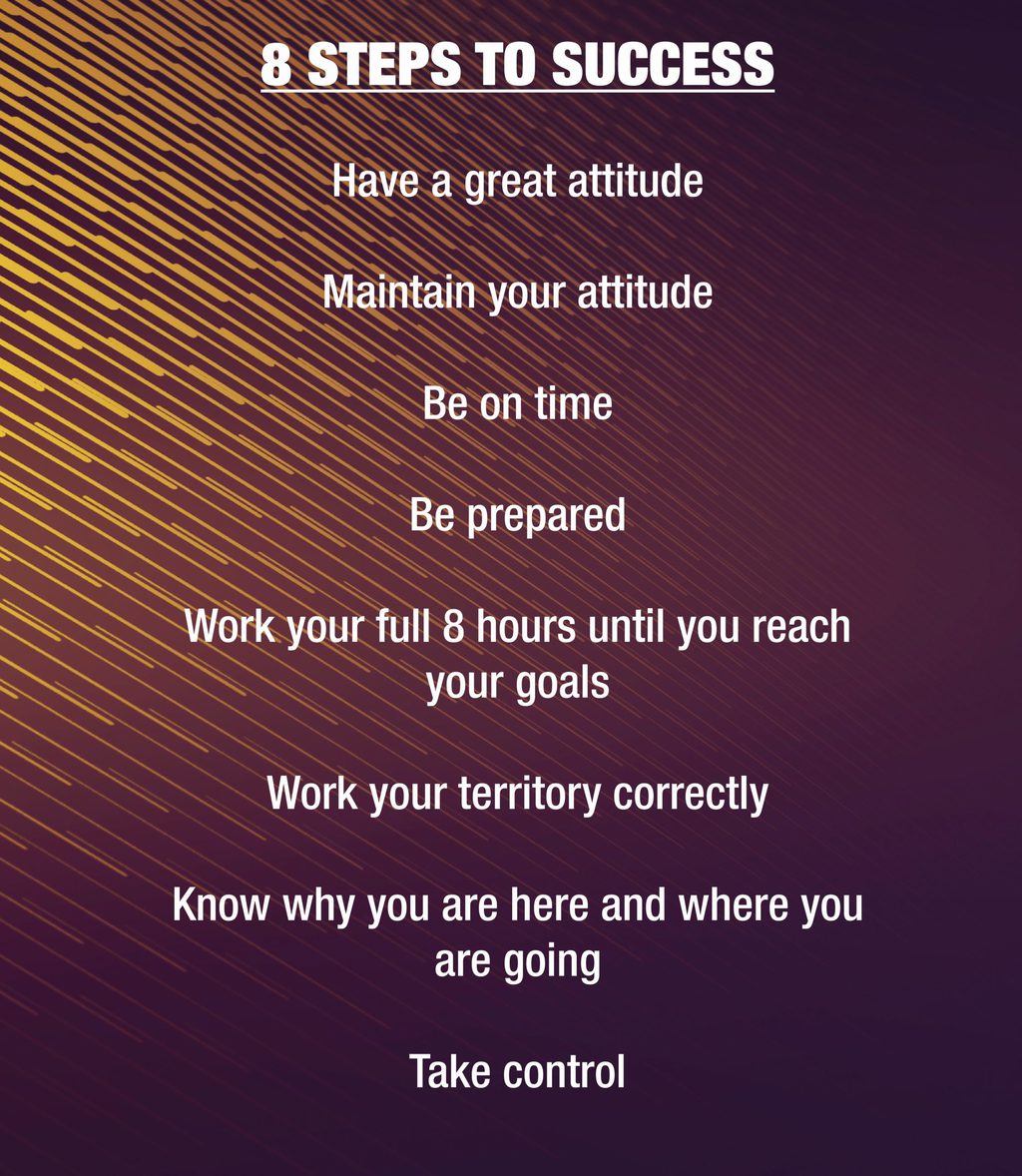

In the earliest days, the founders sat down to write their manifesto – ‘8 Steps to Success’ – in which they outlined their company’s values, even though it was just the two of them. But they deliberately eschewed budgets and financial controls, which they saw as impediments to growth.

“Their belief was that budgets allow too much game playing and that they have negative aspects associated with them,” Associate Professor Kober says.

By this they meant a common tendency of managers to spend ‘budget’ at the end of the financial year in order to receive either the same allocation or increase it the following year, wasting precious resources.

Instead, Company Z focused on looking after their employees better than their competitors in areas such as working conditions and bonuses.

“They paid salespeople higher commissions than competitors, with successful salespeople earning over NZ$100,000. And the employees responded because the owners were looking after them,” Associate Professor Kober says.

During the growth phase, administrative controls in the form of management structure and an operations manual were put in place.

“It was understood that linking compensation to performance could create pressure for people to act in ways their superiors would deem inappropriate. Administrative controls gave notice that some types of behaviour or activities would not be tolerated,” Associate Professor Kober says.

Bucking the trend

At the early stage of company growth, focusing on culture is a highly unusual approach. “Financial controls are usually the first to emerge – even in Silicon Valley start-ups,” Associate Professor Kober says.

Research shows an entrepreneurial company would ordinarily follow a fairly standard trajectory. In the birth stage, the company might have only informal controls and administrative policies and procedures to protect its assets.

As the company starts to scale, it introduces financial planning and forecasting-based financial controls, followed by administrative controls and finally, cultural controls.

But Company Z turned this on its head.

“The two key findings we found in our research were the importance of culture and the importance of keeping the controls in balance, with controls working together interdependently in a complementary fashion,” he says.

As they grew, Company Z continued to bring everything back to their culture and core values. For instance, sales training sessions would be on culture, not achieving budgets.

They had no investors, no bank loans; it was a simple cash business which allowed them to focus on the customer.

One of the founders had experience in call centres and had a marketing mindset. No budgets were set at head office level, although in the following years some of the franchises did quick calculations of budgets for the year ahead.

Finding the balance

To understand the significance of the research, it’s helpful to draw on ‘complementarity’ theory, which originates from economics and investigates how a decision-maker tries to maximise ‘performance’ by (simultaneously) deciding on multiple-choice variables.

Activities are complementary if doing more of one activity increases the returns from doing more of the other activities. Such a theory suits the study of how management controls operate in combination with each other; that is, do the management controls within a package operate independently of each other or are they interdependent, operating together as a system?

Complementarity theory also introduces the notion of balance in understanding how each management control – culture, administrative procedures, financial planning – is constituted.

These management controls can either be in balance – such as when all work interdependently – or off-balance, when one or more obstructs complementary performance.

To stay in control while scaling up dramatically, Company Z maintained a balance by continually reinforcing the tool of culture whenever new management controls were introduced.

The take-out message for early-stage entrepreneurial companies? Designing and demonstrating a commitment to a set of cultural controls and linking these back to other management controls can be the key to staying in control when your company begins to grow quickly.

“In this entrepreneurial case study, the cultural controls came first in the form of a vision statement and core values. These cultural controls were constantly reinforced and built upon,” Associate Professor Kober says.

“As the company grew, it introduced administrative and financial controls to further support its cultural controls.”