Poverty isn’t just a lack of income – it is about being deprived of access to clean water, sanitation, healthcare and education. Countries around the world are re-evaluating how they measure these needs.

Many people may be familiar with the concept of a “poverty line”. Or that living below a certain amount – such as $1.90 per day – constitutes “extreme poverty”. But over the past 20 years, researchers and policy-makers around the world have increasingly recognised that such metrics give an incomplete understanding.

“Income allows people to meet basic needs but at a practical level we find income does not always provide a sufficient representation of poverty,” explains Monash Business School Associate Professor Gaurav Datt, a development economist who has spent a large part of his career researching the measurement and analysis of poverty.

“People may be above the poverty line but still deprived of needs such as housing. So another way to measure poverty is to measure it directly in terms of the ability to meet a number of basic human needs such as access to housing, healthcare, sanitation and education. This is a ‘multidimensional’ approach.”

Associate Professor Gaurav Datt.

From this perspective, income is the means to ends, while the ends themselves are the satisfaction of basic human needs. The multidimensional approach has a direct focus on the ends.

Associate Professor Datt, who is the Deputy Director of the Centre for Development Economics and Sustainability (CDES), is leading a team from the World Bank to help the statistical authorities in Myanmar and the Philippines develop their first multidimensional measures of poverty.

The multi-dimensional approach of using basic human needs is only one framework. The approach can also be founded upon the idea of minimum human rights, and then assessing whether people in a society are able to meet them.

Nobel Laureate and Harvard Professor Amartya Sen also devised a third way of measuring society’s welfare by determining whether people in that society have a certain set of capabilities. These capabilities in turn lead to notions of adequate nutrition, health, education, shelter and so on.

“All of these approaches overlap, and they also overlap with the simple approach of just asking people: ‘what does poverty mean to you?’, which also leads to a similar set of basic needs that people want to be satisfied,” says Associate Professor Datt.

Multidimensional Poverty Index

Recognising the shift in thinking of poverty beyond simple dollar terms, in 2010 the United Nations Development Programme launched its global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) for more than 100 developing countries, with support from the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI).

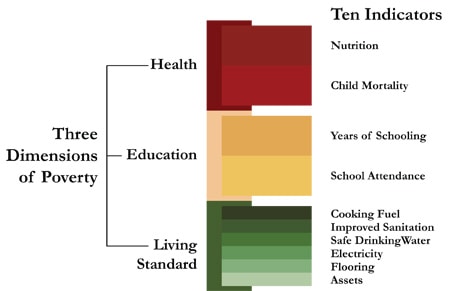

The United Nations’ MPI uses three dimensions and ten indicators. The first dimension is health, with indicators of nutrition and child mortality. Then there is education, with years of schooling and school attendance; and finally living standard, with cooking fuel, improved sanitation, safe drinking water, electricity, flooring material for the house, and assets.

SOURCE: Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

The global MPI is then built from these indicators by assigning them uniform weights: each of the three dimensions have an equal weight, and indicators within a dimension also have equal weights.

While the global MPI has been an important benchmark, many countries that have been developing their own national MPIs and have been using the opportunity to flexibly adapt or refine the global MPI approach.

Alongside, many countries such as Mexico, South Africa, Chile, Ecuador and Columbia have also launched their own national multidimensional indices.

“Once the idea of a multidimensional approach of measuring poverty was launched it gained traction within countries because people readily understand it,” says Associate Professor Datt. “It provides direct information on the areas in which a country is lagging behind.”

Myanmar and the Philippines

In the Philippines, at the invitation of the World Bank, Associate Professor Datt in 2017 held a week-long workshop with 20 staff from the Philippines Statistics Authority in Manila.

The first step is the selection of indicators, then comes the process to determine how to weigh these indicators and how to aggregate them into an index.

“We started off by asking each person in the room to come up with ten things they associated with poverty and to write it on a post-it note. We had around 200 post-its and most fell into obvious categories,” he says.

“Education had the longest list, then a whole bunch related to health and employment and there were fewer mentions of security and assets.”

“Once we came to an agreement on the broad categories, we then thought of two or three indicators which narrowed the concept down. For example, is a person who hasn’t finish primary school in poverty, or should the bar be a person who hasn’t finish secondary school?”

The outcome was 13 poverty indicators which are being used for an initial version of the MPI for the Philippines.

In early October, again at the invitation from the World Bank, Associate Professor Datt held a workshop with the Department of Population in Myanmar.

“Myanmar actually has the unique opportunity to use its census as the basis for measuring multidimensional poverty,” he says.

Whereas usually multidimensional poverty measures are based on household surveys of a few thousand households, Myanmar’s most recent census in 2014 actually asked a number of questions dealing with non-monetary indicators of welfare which can provide enough information to build an MPI using information for the entire population of 51 million.

In the village of Dala, Myanmar, villagers can access the only source of drinking water for one hour daily and are restricted to two buckets per trip.

Different countries, different categories

The Philippines decided on 13 indicators divided into four categories: education; health and nutrition; housing, water and sanitation; and employment and social protection.

Myanmar has initially settled on 14 indicators across education; health and disability and mortality; employment; water and sanitation; housing and amenity; and assets.

There are departures from the UN MPI. For example, while the global MPI does not have a dimension or indicator relating to employment, both the Philippines and Myanmar felt employment was an important aspect of poverty. This is similar to national MPI indices in many other countries.

Also, certain indicators could be given higher or lower weights within an index, Associate Professor Datt suggests. This is best based on people’s own view of the importance of different needs. For example, lack of shelter may be viewed as more important than education within some countries.

Myanmar is currently considering developing weights for different indicators based on a survey of people’s ranking of the indicators.

Making every deprivation count

Once the indicators and weights are decided upon, the next step is how the information can be summarised in a meaningful way. But an area of contention is when people are deprived in more than one indicator.

The United Nations MPI considers a person multidimensionally poor if they are deprived in one third or more of the indicators.

Associate Professor Datt criticises this approach as arbitrary. “When you take this approach you are saying the deprivations of people who have less than a third of deprivations don’t matter and essentially assigning them a zero weight in the index,” he says.

“However if we begin with the notion that all these dimensions are important and all these indicators are important, it seems counter-intuitive then to ignore these deprivations because you have arbitrarily decided people need to have at least one third of deprivations to be counted in.”

For example, he says, 22 per cent of deprivations in India would be ignored because of this cut-off. There is little ethical or practical justification for this. Instead, Associate Professor Datt argues for the use of the ‘union approach’ where every deprivation should be counted.

Street food being prepared in Cebu City, Philippines: access to cooking fuel is an indicator of deprivation.

Is 1+1 more than 2?

Associate Professor Datt also criticises the UN MPI for not incorporating the effect of multiple deprivations within the index.

“The global MPI uses a simple counting approach; but imagine if there are 100 deprivations in a population of 100 people, but we could have a case of the 100 people suffering one deprivation each or ten people each suffering ten deprivations,” he says.

“The global MPI approach considers these two cases as equivalent. The index doesn’t penalise for any concentration of deprivations. What is needed is a distribution-sensitive multidimensional poverty measure.”

This means that poverty measures should take into account that the burden of two or more deprivations for a person is greater than the sum of those deprivations experienced individually. In essence, 1 + 1 equals more than 2.

Associate Professor Datt says the higher the concentration of deprivations for a particular group, the higher arguably is the burden on society.

Though both Myanmar and the Philippines are very receptive to these ideas on the refinement of the standard MPI approach, it remains to be seen how far the final MPIs adopted in these countries will depart from the global MPI.

The development of a national MPI in both countries is subject to a further wider consultation process.