Marketers have been locked into a system that may not effectively measure the impact of all forms of advertising.

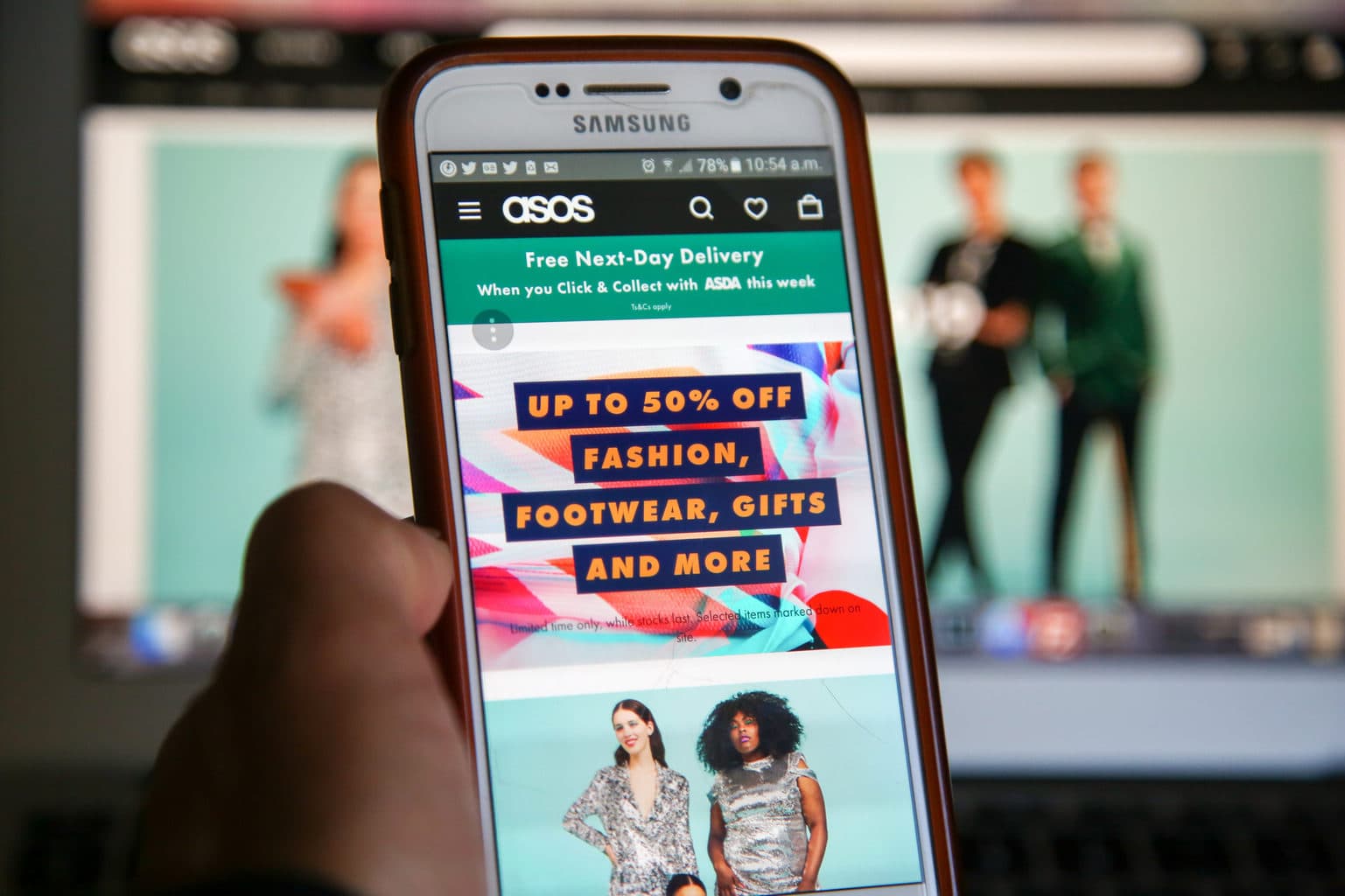

When you buy a product like shampoo online, chances are advertisers are analysing your emails and Google searches to see what form of advertising you saw last before making the purchase.

But did that recent email from Priceline prompt you to buy shampoo, or was it really a catalogue you saw a week ago?

New research from Monash Business School questions how advertisers are measuring the effectiveness of their ads for online shopping purchases. And it says the basis on which they do it, is all wrong.

“At the moment if a consumer buys a new toy online, Google can look at the search patterns that consumer has had over the last few days or whether they’ve had any emails from a store such as Kmart,” says Head of the Department of Marketing, Professor Peter Danaher.

“They use a method called ‘last touchpoint attribution’; that is, the purchase is attributed to the very last touchpoint. So, if the consumer last opened an email about toys, the email gets the credit. If they last did a Google search on toys before making the purchase, Google does.”

The advertising industry has used this method for around the last five years because they want to know which ads can get credit for being effective. It also has the benefit of being very simple.

The problem is, however, that it ignores the effectiveness of certain types of advertising and the ‘carry-over effect’ – or how long consumers remember an ad for.

“Research shows that mail catalogues are a very effective form of advertising and the effect of such an ad may last for a few weeks,” says Professor Danaher.

Yet the attribution method ignores this fact. It also ignores that more than one type of ad can spark a purchase.

“The attribution method is really biased in favour of media that comes more often such as email,” he says.

“It means email gets a lot of attribution which is misleading to advertisers.”

Future media allocation

And the problem is compounded because this data often informs where money is spent on which kind of advertisements.

“There is a temptation in this kind of modelling to use attribution percentages as the basis for future media allocation,” says Professor Danaher.

“Attribution is an inherently descriptive approach capturing how much of a role each medium has played in driving (past) purchases,” he says. “However, this does not mean that attribution should be used for allocating a budget across media to maximize profit.”

For example, if 80 per cent of all purchases of face cream is attributed to emails and 20 per cent to magazines and both forms of advertising cost the same.

It would be wrong to spend four times as much on email face cream ads as magazines – because attribution creates the illusion that the number of times a person has been exposed to the type of ad means it is very effective and should receive more investment.

Professor Danaher argues that instead allocation decisions should be made using formal profit optimisation.

This method takes into account the cost of a method of advertising when allocating budget to it and it also links the incremental impact of different types of advertising on the actual purchase outcome.

“Even if there is a zero purchase probability effect of a medium, attribution methods that are based on counting the number of exposures prior to making a purchase will attribute a significant portion of the purchase to that medium,” he says.

It gives skewed information to advertisers and favours emails which have the benefits of being cheap and come out at 10 or 12 times the rate of catalogues – a much more expensive form of advertising that is mailed perhaps once a month.

More than one type of advertising

It can also imply that television and magazine advertisements are useless, which Professor Danaher says, the research shows this is far from the case. It also favours Google searches, which works very well for Google which has an incentive to sell the attribution method.

“What we propose is a more econometrically sound method,” says Professor Danaher.

“Everyone in academic circles sees the last touchpoint attribution method as flawed but we argue that the concept itself is wrong.”

His new method takes into account more than one type of advertising that may lead to a purchase and the incremental contribution each form takes. It also takes into account the carry-over effect, or how long the effectiveness of a particular form of advertising may last.