How much superannuation is enough to retire? With the pandemic biting into retirement savings, we will need more than we think.

COVID-19 has percolated through to global retirement savings, making them less secure, according to the 12th annual Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index.

As a result, the provision of adequate and sustainable retirement incomes over the longer term has also changed.

Just how much superannuation do you need to support a comfortable retirement in Australia?

The last time Australia’s super industry tried to provide guidance on this question, it came up with a figure of $545,000 for a single person retiring at 66. The Australian Government came up with a similar number – $570,000.

COVID-19 Financial turmoil

But should Australians rely on these figures – particularly after the economic and financial turmoil brought on by COVID-19?

Dr Ummul Ruthbah, senior research fellow at the Monash Centre for Financial Studies in Melbourne, has serious doubts about the reliability of the official figures after completing a major study into the financial needs of Australian retirees. Her findings have been published in a research paper The Retirement Puzzle.

Dr Ruthbah says that, contrary to official guidance, most Australians would need a much higher super balance than $570,000 to ensure a long and comfortable retirement – and to avoid running out and having to rely on the age pension.

And in another finding with dire long-term implications for governments, Dr Ruthbah found fresh evidence that pension eligibility rules are creating perverse incentives for Australians to deplete their superannuation accounts early in order to qualify for government support.

Why $570,000 might not be enough

Through various rules and tax incentives for superannuation – including the 9.5 per cent super guarantee – the government aims for as many people as possible to achieve full or partial independence in retirement.

In its most recent projectionsAustralia’s super peak policy, research and advocacy body,ASFA said a single male who lives to 86 could retire comfortably with a starting super balance of $545,000 while spending $44,183 a year. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission produced similar numbers, suggesting $570,000 would sustain someone spending $41,515 a year for 30 years.

To test these projections, Dr Ruthbah set up and analysed a series of modelled scenarios for individuals as they move through retirement.

Her modelling took account of likely variations in macroeconomic conditions – including interest rates, market performance and inflation – and increasing life expectancy.

She assumed the retiree is a single homeowner with a typical super investment mix of 60 per cent equities and 40 per cent defensive assets and allowed for various starting balances and drawdown strategies. She then generated simulated outcomes for 10,000 possible scenarios and averaged them.

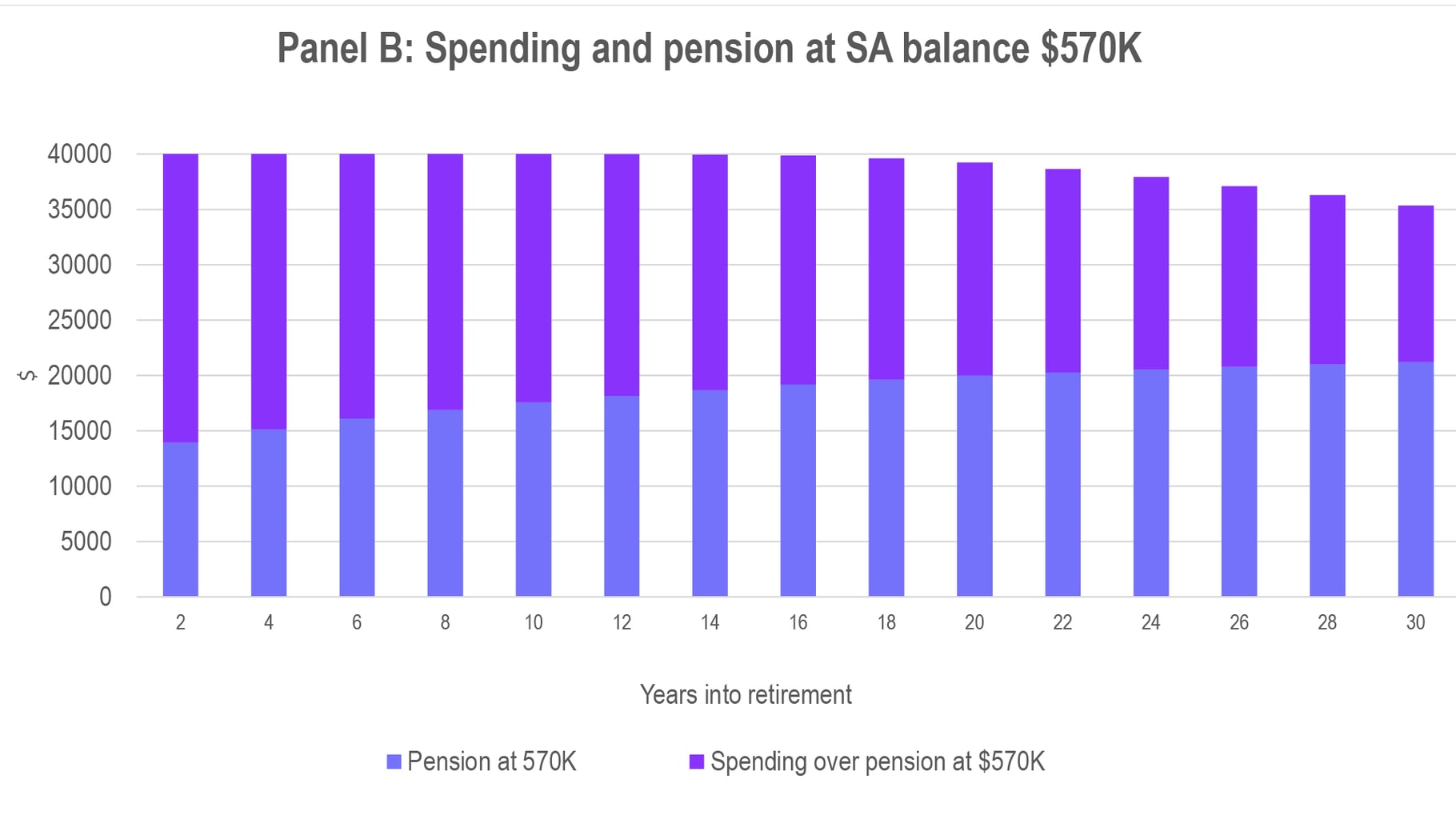

The results cast significant doubt on the official comfortable retirement projections. ‘’My study’s simulation model predicts that a retiree with a $570,000 portfolio has a 30 per cent chance of running out of money within 30 years and a 15 per cent chance of having to rely fully on the age pension after just 25 years,’’ she says.

Tellingly, most retirees have superannuation balances far below $570,000. The average balance of retirees aged 64-75 in 2017-18 was just over $400,000, while the median was $225,200.

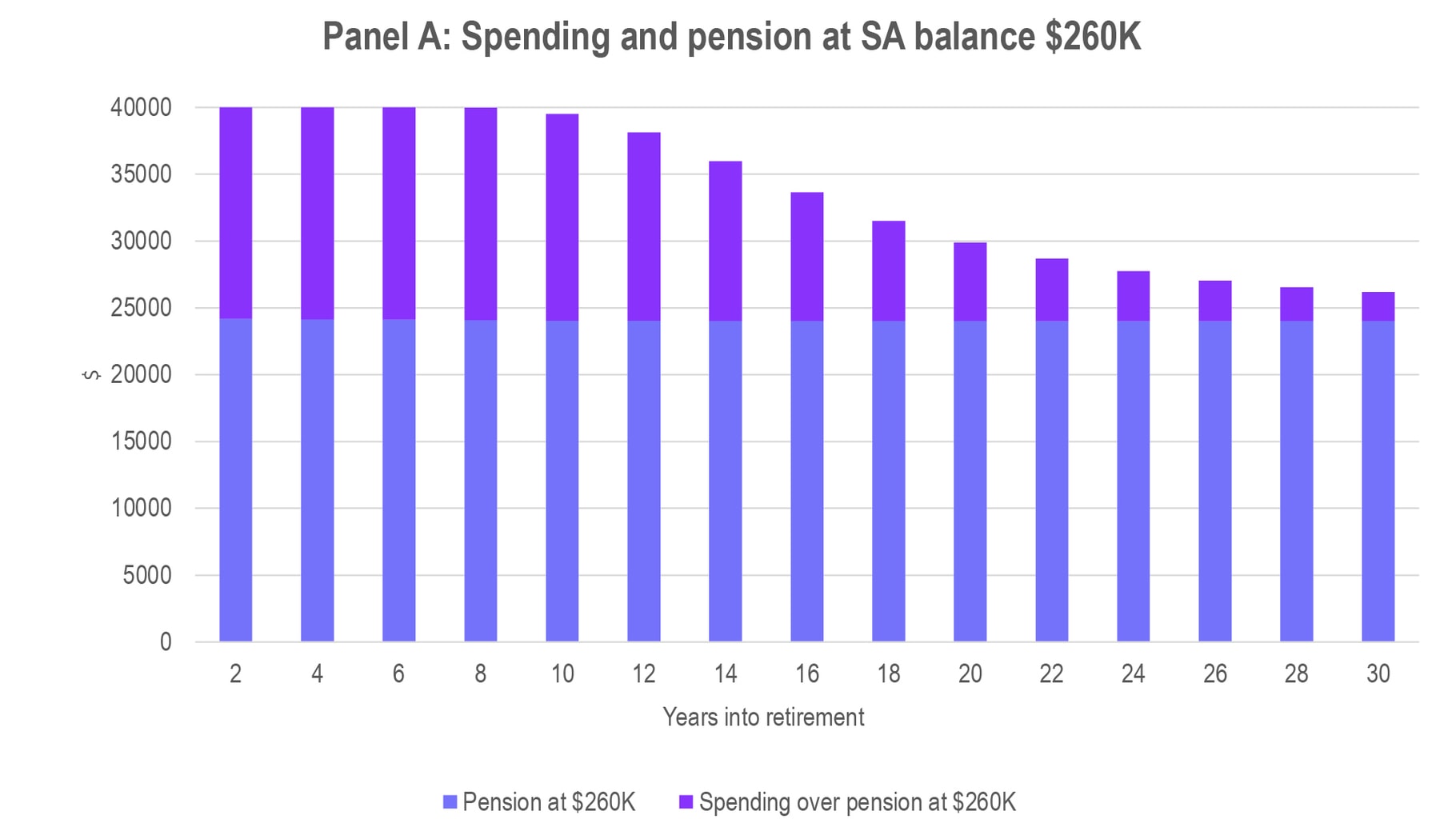

The study’s simulation model shows a retiree with $400,000 in super has a 20% chance of running out of money after 20 years. Those starting out with $260,000 – just below where pension starts tapering off – have a 33% chance of running dry after 15 years.

Panels A and B show the predicted spending trajectories of retirees with starting super balances of $260,000 and $570,000, and their relative reliance on super savings and pension over time.

Incentive traps

A concerning aspect of Dr Ruthbah’s research is its exposure of incentive traps, whereby retirees and pre-retirees have incentives to run down their super balances or to invest in assets excluded from the pension eligibility test – such as home renovations – to qualify for more age pension.

Dr Ruthbah calculated that pre-retirees with more than $350,000 in super are among those facing the incentive trap. Similarly, people already in retirement with more than $350,000 in super have incentives to deplete it on unproductive or unnecessary consumption to qualify for more pension.

How much is enough?

A key element of Dr Ruthbah’s modelling is its accounting for uncertain future investment returns, with both upside and downside risk. On the downside, her modelling suggests people with a super balance of $650,000 – or even as much as $800,000 – might struggle to meet their financial needs if the timing and direction of market conditions turn out to be unfavourable.

Her findings address the current economic slump and turmoil in markets resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, which has impacted negatively on the super balances of many retirees. In the post-COVID-19 era, she said the rosy projections for people retiring on $570,000 seemed improbable ‘’based on historical performances of equity and bond markets’’.

World’s-best practice?

While Australia’s retirement income system is regarded by some as among the best in the world, Dr Ruthbah’s study exposes its flaws, with potentially drastic implications for future government finances.

‘’In addition to the likelihood of more retirees qualifying for the age pension than anticipated, many retirees will be adding to pressures on the pension system simply by living longer than their parents,’’ she says. ‘’And these financial demands will be building at a time when governments are likely to be still dealing with the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.’’